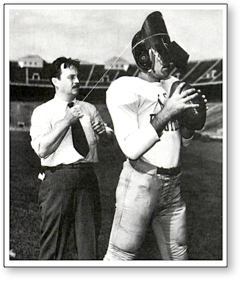

Above OSU art professor Hoyt Sherman (left), with OSU football quarterback Pandel Savic, demonstrating the “flash helmet,” a modified football practice helmet with a visor that Sherman could open and close very quickly by means of a cord. During the brief exposure, the passer had to spot the receiver, then throw the ball while the visor was closed. Below right is Sherman’s drawing of the flash helmet.

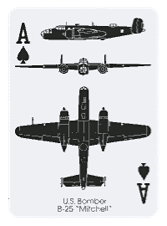

Above During World War II, aircraft and ship identification silhouettes (in the form of decks of playing cards) were widely distributed to US citizens and military personnel.

![Michael Torlen (2013), “Hit With a Brick: The Teachings of Hoyt L. Sherman” in Visual Inquiry: Learning and Teaching Art. Vol 2 No 3, pp. 313-326—

“[At the first class meeting] Sherman handed out a course outline and began his lecture. Then he turned and walked over to a table stacked with a variety of materials, including a pile of red bricks. Seemingly distracted, Sherman stopped discussing his syllabus ans started seraching for something beneath the brick pile. He stacked and re-shuffled the bricks, sorting and clinking them loudly against each other, until he suddenly turned and hurled a brick directly at our heads.

Certain he had aimed the brick at me, I scrambled to get out of the way, murmuring, ‘Is this guy crazy? Sherman was laughing. The brick he threw was a piece of foam rubber, the same size as the other bricks, painted brick red. Sherman explained that we were unable to distinguish the foam rubber brick from the cluster of real bricks, because our past experience, our associations and our memory of bricks influenced us. Our reactions developed from the false assumption that similar things are identical” (p. 314).](DrawingInDark_files/shapeimage_14.png)