DESIGNING FOR

JERZY KOSINSKI:

THE EMBELLISHED BIRD

An Essay by Roy R. Behrens

An earlier, different version of this, titled “Cover Story,” was published in PRINT magazine (New York).

Nov-Dec 1996, pp. 24-25ff.

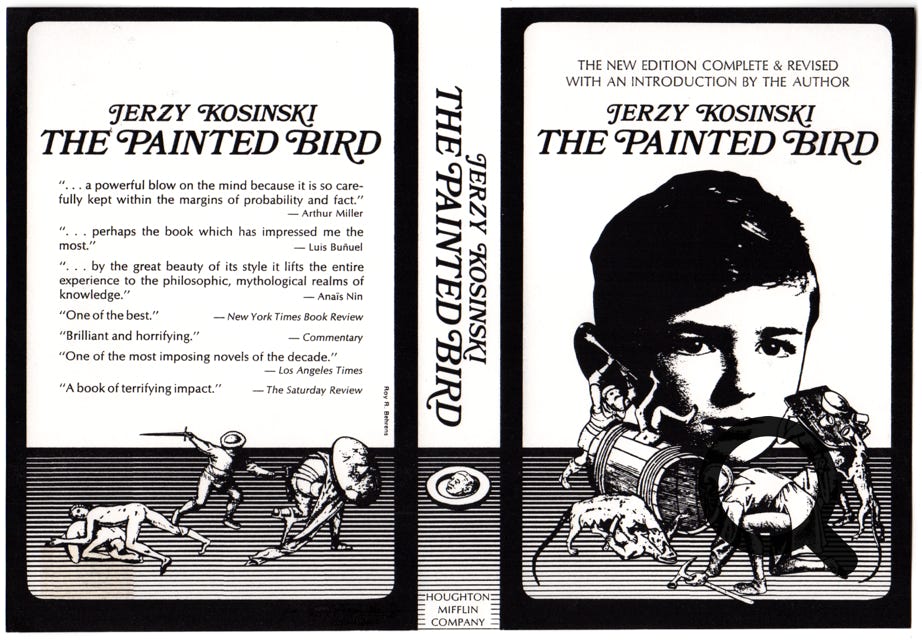

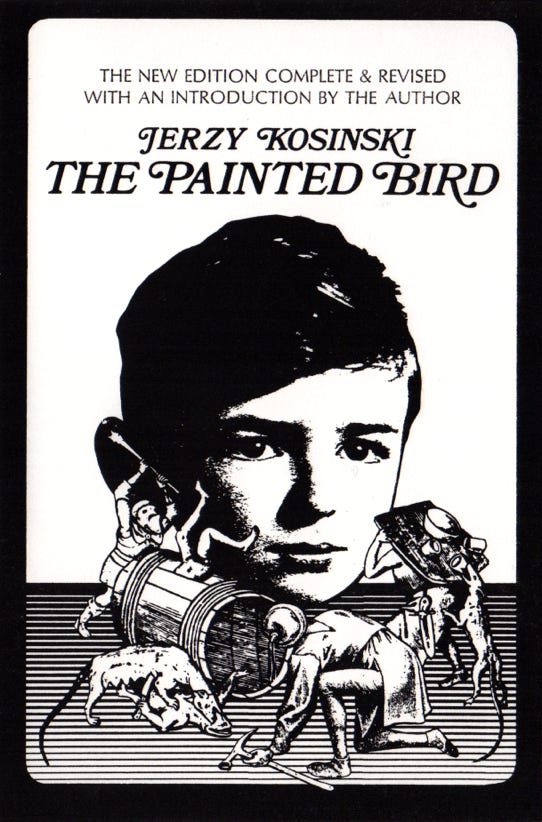

dust jacket for Jerzy Kosinski’s The Painted Bird (Houghton-Mifflin, 1976)

We have only recently learned that a film version of The Painted Bird has been completed. Produced and directed by Václav Marhoul, it will be released in the near future. Go to this link and to this official site for more details.

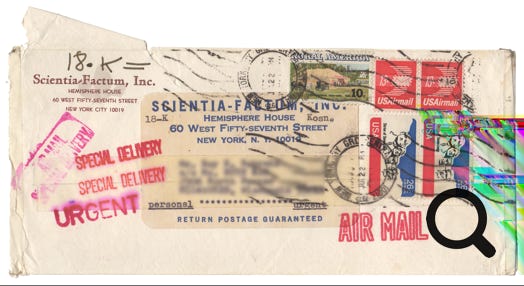

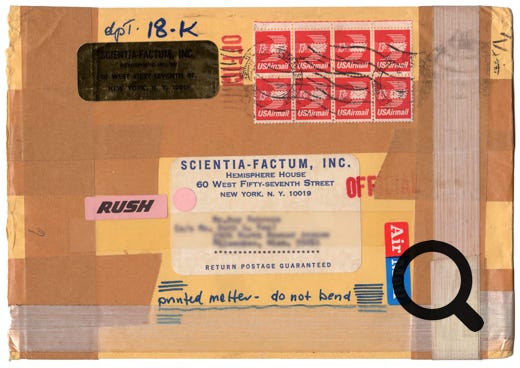

Above In keeping

with his penchant for mystique and intrigue, any envelopes from Kosinski were heavily embellished with rubber stamps, stickers and notations.

Right

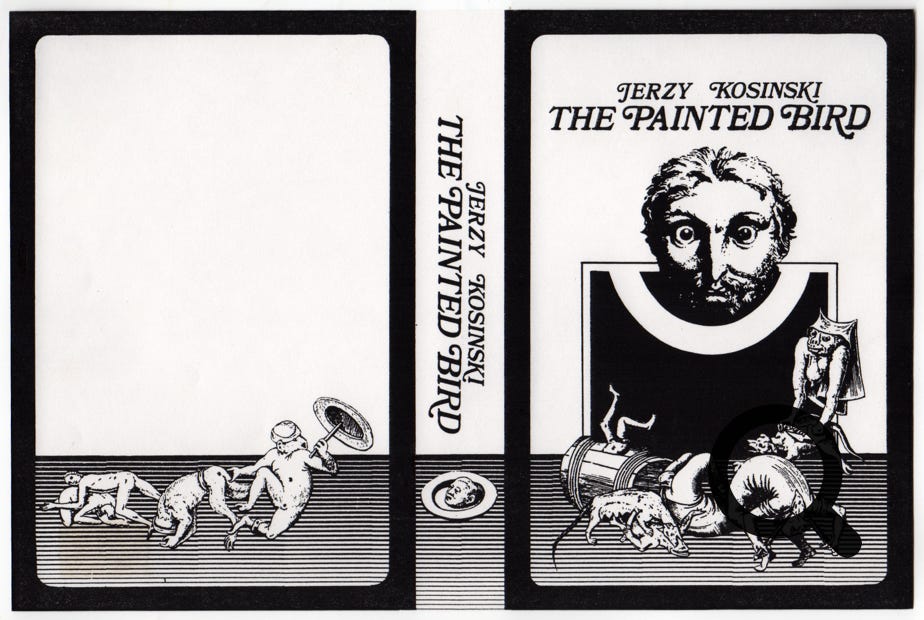

The initial dust jacket proposal.

Right

A detail of one of the photographs supplied by Kosinski, showing himself with his head shaved.

Right The final dust jacket, as published.

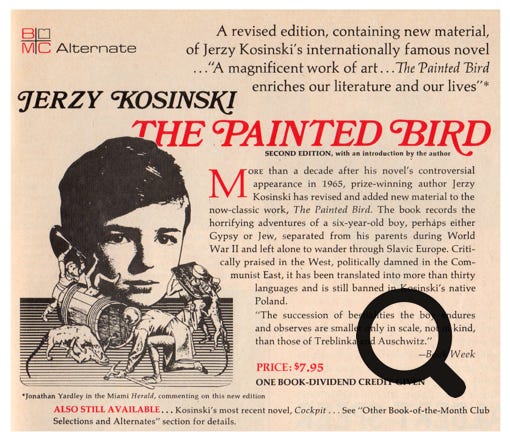

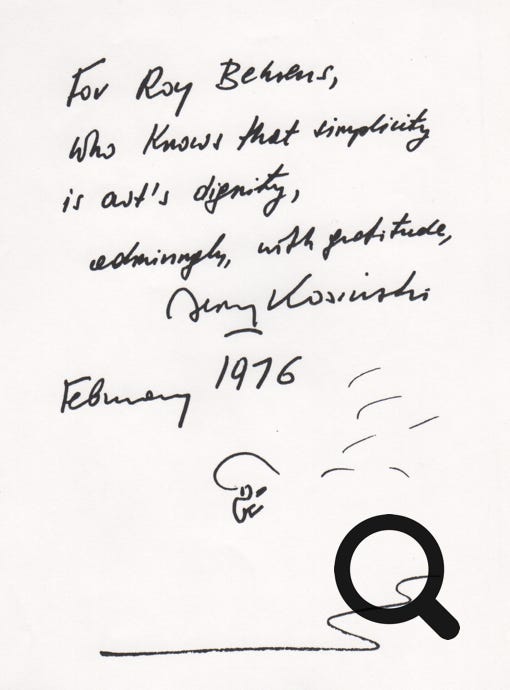

Above The announcement of the book by the Book of the Month Club. Below An inscription from the author to the designer

In the early 1970s, I worked with a literary quarterly called the North American Review. Edited by Robley Wilson, and published at the University of Northern Iowa, it was only moderately funded, yet it quickly came to be (at that time) a nationally-prominent, award-winning literary magazine. Through that position, I became acquainted with Jerome Klinkowitz, a young literary critic who was teaching in the English department on the same campus. Among our shared interests were the short stories of Donald Barthelme,* which were often amplified by Barthelme’s Max Ernst-like collages, interwoven with the text. I had first learned of Barthelme's work in 1971 in a literature class as a graduate student at the Rhode Island School of Design.

In 1974 Klinkowitz suggested that he and I collaborate on an unorthodox critical essay about Barthelme's short stories. Klinkowitz would put together the text for the article, which I would then embellish with collages made of 19th-century steel engravings, resulting in a parody of Barthelme's own stories.

Titled "Donald Barthelme's SuperFiction," our article was published in 1975 in a literary journal called Critique, and then reprinted the following year in Richard Kostelanetz's Younger Critics of North America (Milwaukee: Margins Press). Soon after, Klinkowitz and I again collaborated, using the same approach, this time on The Life of Fiction (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976), a book about Barthelme and eleven other pioneers of postmodern fiction.

Also of interest to Klinkowitz was the fiction of Jerzy Kosinski (born Josek Lewinkopf), a Polish-born Jewish-American novelist who became famous in 1965 with the publication of The Painted Bird, a haunting novel about a dark-haired, olive-skinned six-year-old boy who is separated from his parents for five years, and wanders through remote villages in Eastern Europe during World War II. Victimized by superstitious peasants, who are fearful of harboring Gypsies or Jews, the boy witnesses and/or is subjected to scenes of cruelty, violence and perversity so unspeakable that he becomes mute.

As a literary scholar, Klinkowitz had interviewed Kosinski in 1971, in an exchange that supported the general belief that The Painted Bird, while advertised as fiction, was largely autobiographical. As a child, Kosinski (or so it was thought at the time) had also been separated from his parents during the German occupation of Poland, had witnessed wartime violence, and had lost the ability to speak until, at the war's end, he was reunited with his parents.

Some critics saw The Painted Bird as a Holocaust document, comparable to The Diary of Anne Frank. In 1965 it received the Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger, the French award for the best foreign book of the year. In the decade that followed, Kosinski published three other novels: Steps, which won the National Book Award; Being There (later made into a popular film starring Peter Sellers); and The Devil Tree.

In 1970 he received the award in literature from the National Institute of Arts and Letters. In addition, he claimed that he narrowly missed being killed by the Charles Manson gang when he was expected, but did not arrive, at the home of Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate on the night in 1969 when Tate and her house guests were murdered.

In 1975, Dan Cahill, head of the English department at UNI, had also been interested in Kosinski's writing. In June of that year, Cahill was in New York interviewing Kosinski, when the novelist asked him to pass on a message to me. He had seen my collages in our essay on Donald Barthelme, and he wanted me to design the cover of the European paperback of his lastest novel, Cockpit.

When Cahill returned to Iowa, I sent Kosinski a letter, confirming my interest in the project, and inviting him to call to talk. When he phoned on June 25, his request had changed. He now wanted me to design the dust jacket of a special 10th-year edition of The Painted Bird (Houghton Mifflin, 1976), and (potentially) the American paperback of Cockpit.

Our phone conversation was pleasant and brief, mostly devoted to his reflections on The Painted Bird and his dissatisfaction with earlier covers. I believe we also talked about the novel's affinity with the nightmarish imagery of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel.

At the time of that first conversation, I hadn't read The Painted Bird. But in the weeks that followed, I read it closely, sampled reviews, and discussed it with various colleagues, especially with Klinkowitz, who loaned me copies (with covers intact) of earlier editions. After talking to Kosinski’s editor at Houghton Mifflin about the size, text and other requirements, I began to make thumbnail sketches and collage mock-ups. Early in the process, I made a conscious decision to work in black and white: to convey the graphic starkness of the novel, and to enable it to stand out on the shelf in the bookstore.

The title of The Painted Bird is taken from an episode in Chapter Five, which describes a peasant named Lekh who makes his living by trapping wild birds and selling them to villagers. In moments of inexplicable rage, he sometimes seizes a captured bird, ties it to his wrist, and paints its entire body in bright, vivid colors. He then releases it into the air, whereupon the bird rejoins its original flock. However, the other birds become confused by this bizarre appearance of this interloper, and instead of welcoming it as one of their own kind, they attack and rip it to pieces.

What an interesting title, I recall thinking, as succinct and memorable as a particularly well-designed logo. The boy is like the painted bird, as human as those who surround him, yet unrecognized and attacked because of his ethnicity. I also concluded that it was not just a book about the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe during World War II, about the capabilities of any society at nearly any moment. I thought that Kosinski intended to show that each of us is susceptible to persecution by our own kind, perhaps because we are Gypsies, Jews, Asians, African-Americans, and others, or because of our gender, religious beliefs, sexual inclinations, and so on. At the very same time, we ourselves are also susceptible to joining in with the mob, and contributing to the savage attacks on the "painted birds" around us.

In Kosinski's novel, the boy has dark, distinctive eyes. Whenever he looks at the peasants, they suspect him of casting a spell because he has an "evil eye." In advance of reading this book, by coincidence I had researched and written about the responses of human beings and animals to certain basic visual forms, such as concentric circles, bilateral paired circles, and eyespot markings (called ocelli) on the wings of butterflies and moths. I had published several articles on the subject, including one describing my classroom demonstration of how to "hypnotize" a live chicken, using a stuffed owl, my own stare, and a drawing of bilateral circles. More generally, I was aware of the conspicuousness of target-like concentric shapes, and of the age-old apprehension about the evil eye.

After working on the cover for several weeks, I came up with a layout that I thought might be workable. It combined three ingredients: the metaphorical equation of the boy and the bird; the menacing stare of the evil eye; and the animalistic perversity of the peasants. The beak-nosed, wide-eyed human face in the center of the cover was based on a 17th-century drawing by Charles Le Brun, a comparison of human and animal physiognomy I had first encountered in Claude Lévi-Strauss' The Savage Mind. It didn't concern me that the bearded face was not that of a child, since the book was not simply or only about a particular child, but about each and every one of us at any age.

I shipped the first cover proposal to Kosinski on July 16. He called six days later, and we talked about reactions to the cover, both his and those of his various friends whom he had shown it to. He said they all agreed that, while they liked the overall layout and the stark use of black and white, they had doubts about the imagery. They objected to the omission of the child, and they thought that the wide-eyed Le Brun portrait would tend to be wrongly interpreted as a traumatized concentration camp figure.

Then, in the same conversation, Kosinski explained he was sending me photographs from his childhood. "One of them," he said, "is a photograph of me as a young boy with my head shaven, just before I was sent off to [he chuckled] the monsters. These may provide some visual trigger."

When Kosinski's envelope arrived, it contained faint photocopies of about a dozen views of bearded Eastern European peasants, thatched huts, marshes, and so on. Among the images were three formal photographs of Kosinski as a child. On the first, he had written in pencil "Summer 1939" and attached beneath it a typewritten label that read "Kosinski (age of six). One month after this picture was taken, in the Summer of 1939, the War began." This photograph was encircled by five other snapshots, connected by a pencil line and labeled "Winter 1939," including a group photograph of two peasant men and seven children, one with his head shaved.

In the same package, there was another portrait of Kosinski, slightly older. Beneath it was this label: "At the age 11, in the orphanage in the Red Army liberated part of Poland (1944). He was mute. Two years after this picture was taken (by the authorities), he was reunited with his parents."

For the next few weeks, I worked on alternative mock-ups, trying to incorporate the photographs he had sent. After repeated failures, I impulsively threw out the initial cover design and focused instead on an offhand remark by Kosinski, in which he said that society had changed since the book's initial publication, and that one could now feel free to show explicit violence.

As a result, in the second proposal (which I sent to him in several versions), I used a very disturbing image of a child from a 19th-century book on surgery, with a face that was partly destroyed by disease. I combined this image with engravings of bones, teeth and other human remains. Frustrated, and not at all pleased with this second set of proposals, I continued to think that the first was the best.

When Kosinski called next, he said that he may have misled me, and that I was wrong to abandon the initial cover. He suggested that I reconsider some of the foreground figures and replace the Le Brun face with the contrasting, innocent head of a child. As for a suitable image of the boy in the novel, he added, one of his friends had surprisingly said that I should use one of the photographic portraits of the young Kosinski. Did that interest me? If so, he could provide me with a better print of the portrait that was taken in 1939.

The idea of using his photograph had occurred to me, but I had quickly dismissed it. I knew of course that the novel was rumored to have been autobiographical. But Kosinski's comments to questioners had been ambiguous, even evasive, so I assumed that he wanted to stress the distinction between factual aspects of his childhood (whatever they were) and the fiction of The Painted Bird.

In the end, I used his photographic portrait, and soon after we reached an agreement about the final version of the dust jacket. I met him in person later that year when he lectured on campus. As anticipated, the book appeared in the spring of 1976, and was chosen as a Book of the Month Club Alternate.

In the ensuing years, Kosinski wrote four other novels (Blind Date, Passion Play, Pinball, and The Hermit of 69th Street). He also wrote the screenplay for the film version of Being There; became a frequent guest on the Tonight Show; and appeared in the role of Zinoviev, Lenin's collaborator, in Warren Beatty's movie Reds.

In 1979, Jerome Klinkowitz traveled to Poland. There he spoke to various people who claimed that Kosinski had fabricated the events of his childhood, as well as certain aspects of the German occupation. That same year, he published an article titled "Betrayed by Jerzy Kosinski" in which he reexamined his interview of eight years earlier, and concluded that he had been hoodwinked about the factual basis of The Painted Bird.

A far more damaging expose, by other authors, titled "Jerzy Kosinski's Tainted Words," was published in the Village Voice in 1982. It suggested that some of Kosinski's novels, including The Painted Bird, had not been written solely by him, but in collaboration with clandestine translators and editors, some of whom verified the accusation.

In part because of ill health, Kosinski took his own life in his New York apartment on May 3, 1991. In a suicide note, he said "I am going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call it Eternity.” His tragic death provoked speculation about the circumstances of his childhood, the authenticity of The Painted Bird, its authorship, and the reasons for his suicide.

Among the books about his life is James Park Sloan's Jerzy Kosinski: A Biography (New York: Dutton, 1996). Whatever else happens to Kosinski's reputation, wrote Sloan, The Painted Bird will endure: "Odd in every respect—its expansion of experience into a surreal inner theatre, its construction with the help from editors and translators, its lack of dialogue, and its existence at the shadowy border between fiction and personal statement—it remains a major aesthetic response to the Holocaust and a provocative documentation of the complex and reverberating consequences of violence and evil."

* Pertaining to the writer Donald Barthelme, there is a fascinating, if bizarre, essay by Paul Limbert Allman that appeared in Harper’s Magazine in December 2001, pp. 69-72, in which the author speculates that Barthelme may have been somehow responsible for the strange attack on CBS newsman Dan Rather in 1986. In news reports of that NYC street incident, it was said that Rather was approached by two men, who asked him “What is the frequency, Kenneth?” and then chased and beat him. Allman points out that Bartheleme and Rather were the same age, that both grew up and worked as journalists in Houston, and that characters named Kenneth and Dather, as well as the exact phrase “What is the frequency?,” occur in Barthelme’s stories. Barthelme died in 1989.