Iowa WPA Artist Robert Tabor

A Depression-Era Painter from the Midwest

This essay was published initially as a catalog essay for the exhibition Four Seasons on an Iowa Farm: The Paintings of Robert Tabor at the James and Meryl Hearst Center for the Arts (Cedar Falls IA), 1999. Copyright © by Roy R. Behrens. A revised version, titled “Four Seasons on an Iowa Farm: The Paintings of Robert Tabor,” was later published in Iowa Heritage Illustrated. Vol 81 No 1 (Spring 2000).

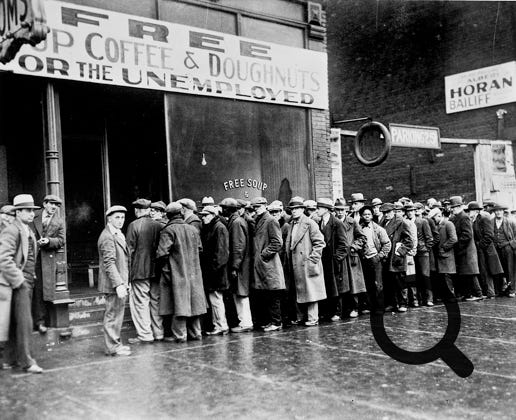

THE GREAT DEPRESSION began in the US with a devastating crash of the stock market on October 24, 1929, a day now infamously known as Black Thursday. Thousands of people lost their investments, and in the aftermath, homes and farms were repossessed, banks failed, and as companies cut back or went out of business completely, millions of Americans became unemployed.

As conditions worsened, the homeless resorted to living in shacks (in shantytowns called “Hoovervilles”) and were fed in public soup lines. Advised that Capitalism should be left to correct itself, Iowa-born US President Herbert Hoover intervened slowly and reluctantly, with the result that he lost by a landslide in the 1932 presidential election. Chosen instead was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the exuberant New York governor, who promised the American people “a new deal.” “The only thing we have to fear,” he declared at his swearing-in, “is fear itself.”

In the first few months of Roosevelt’s administration, he ended the prohibition of alcohol, shifted responsibility for aiding the poor from the states to the federal government, and laid the groundwork for a cluster of regulatory and public works programs, among them the National Recovery Administration (NRA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). He also set up agencies by which jobless people in the arts could be commissioned by the federal government to work on public arts projects. Included among these agencies were the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), the Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP), the Works Projects Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA / FAP), the Federal Music Project (FMP), the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), and the Federal Writers Project (FWP).

In 1933, in the midst of all these efforts, in the small midwestern community of Independence, Iowa, a traveling salesman named Robert Tabor lost his job with a Cedar Rapids-based paint company. Married with three children, the 51-year-old Tabor had worked in his earlier years at a local drugstore owned by his family. But he also dabbled in photography. In fact—or so he later claimed in a newspaper interview—he had invented “the first 3-D slides” and, prior to World War I, a “system of visual education” for which he had “exclusive rights from big publishing houses and endorsements of state boards of education.” But then “the war blew it all up!”

Tabor had never been formally trained in art. But he had once visited the Art Institute of Chicago and had often looked at portfolios of art works at the Independence Public Library, where his sister, Neva Tabor, was the librarian. It may have been in 1930 that he visited the Art Institute, because that was the year in which a prestigious bronze medal had been awarded to a painting by a fellow Iowan, American Gothic by Cedar Rapids artist Grant Wood.

It may have been during that visit that Tabor purchased a reproduction of another work from Art Institute’s collection, a seascape by Winslow Homer, titled The Herring Net (1885). It was that framed reproduction that was damaged beyond repair when it fell from a nail in the living room wall of Tabor’s home in 1933, while he was out job searching. Annoyed by the empty spot on the wall, Tabor decided, regardless of his lack of training, that he would replace the Homer reproduction with a painting of his own, a proposal his family responded to with (as he recalled) “zero enthusiasm.”

In December of the same year, Tabor’s wife Ruth saw a newspaper article on the formation of the Public Works of Art Project. One branch of FDR’s assistance plan, the PWAP was a six-month program that provided jobs for nearly 4,000 unemployed American visual artists, who were paid from $26.50 to $42.50 per week for the decoration of public buildings and parks. In addition to financial need, anyone who applied to the program had to demonstrate their artistic ability to each state’s program director. In Iowa, the director of the PWAP was Grant Wood.

At his wife’s urging, Tabor applied to the program. When he showed Grant Wood his paintings, he was at first rejected. But Tabor persisted. Their conversations continued, and Wood eventually gave in. “Mr. Tabor, it’s against my better judgment,” Wood said (as Tabor later recalled), “but I will try you on one easel piece [during a trial period of one month]. If it is not up to standard, however, we will be forced to drop you. I simply can’t turn anyone down in times like these.”

One month later, Tabor delivered a completed painting, titled Vendue, depicting the sale of an Iowa farm. Admired as much for its subject as for its artistic qualities, the painting (the original of which is assumed to be lost) not only qualified Tabor to participate in the arts assistance program, it also brought him some national recognition.

When entered in a government-sponsored competition with 15,000 other PWAP artworks, his painting was one of 600 chosen to be exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in May 1934. The event was attended by FDR and Mrs. Roosevelt, who chose a number of works for subsequent display in the White House. Tabor’s painting was among those selected, and (as some people claim) it may have remained there until the late 1940s or early 1950s (although, according to existing records, it was never officially listed as White House property).

As Tabor surely realized, the heartrending scene in the painting was one of the chief reasons for its popularity. Years later, in an article in Coronet magazine, titled “The Vendue Story,” Tabor gave most of the credit for the choice of subject matter to Dr. Joseph McGrady, a blind physician and farm manager from Independence. (Years earlier, McGrady had also contributed to the artistic development of another resident of Independence, William Edwards Cook, who later moved to Paris and became one of Gertrude Stein’s closest, most enduring friends. Cook was also an early client of the architect Le Corbusier, who designed his Cubist residence called Maison Cook or Villa Cook.)

It was Doc McGrady, said Tabor, who advised him to use a bank’s foreclosure of a farm as the painting’s subject, and who also provided its enigmatic Dutch title, a term that alludes to both traitors and sales. “You are going to tell our government,” McGrady told him, “from the President down, the tragic condition of the Midwest. You are going to paint a farm sale. That epitomizes it all. Iowa today is just one big farm sale.”

A year after the exhibition, Tabor received a letter from someone in the Roosevelt administration, saying that the painting had “played its part in crystallizing government policy during a great national crisis.” Even more notable for the aspiring middle-aged artist, his painting was rated “by Eastern critics” as being among the top twenty-five pieces in the Corcoran exhibition, and by the director of the Museum of Modern Art (where it may also have been exhibited) as “among the finest and most sensitive in the show.”

Buoyed by his sudden, dramatic success, Tabor would continue to paint for the remaining four decades of his life. Soon after his completion of Vendue, he was commissioned by the government (as part of the Works Progress Administration) to paint a mural for the new US Post Office in Independence, where it is still on public display. Titled Postman in Snow, it records the torturous wintry ordeal of a local mail carrier (it was an Independence postman named Warren Sackett) as he delivers the mail in an Iowa blizzard.

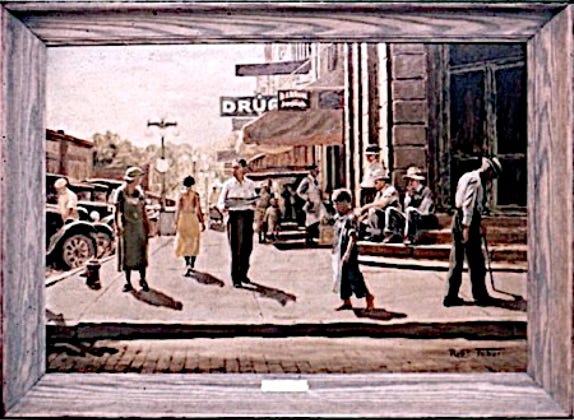

In 1934, inspired perhaps by the vidid detail of Sinclair Lewis’ novel Main Street (1920), a best-selling controversial view of small-town Midwestern values, and in advance of Grant Wood’s illustrations for a new edition of that book (1937), Tabor created his own interpretation of the same subject, in which he recorded the characters on “the bank corner” at the intersection of Main Street and Highway 150 in Independence (looking west toward the Farmer’s State Bank). That painting, itself titled Main Street, was reproduced in the New York Times as an illustration in its Sunday magazine section.

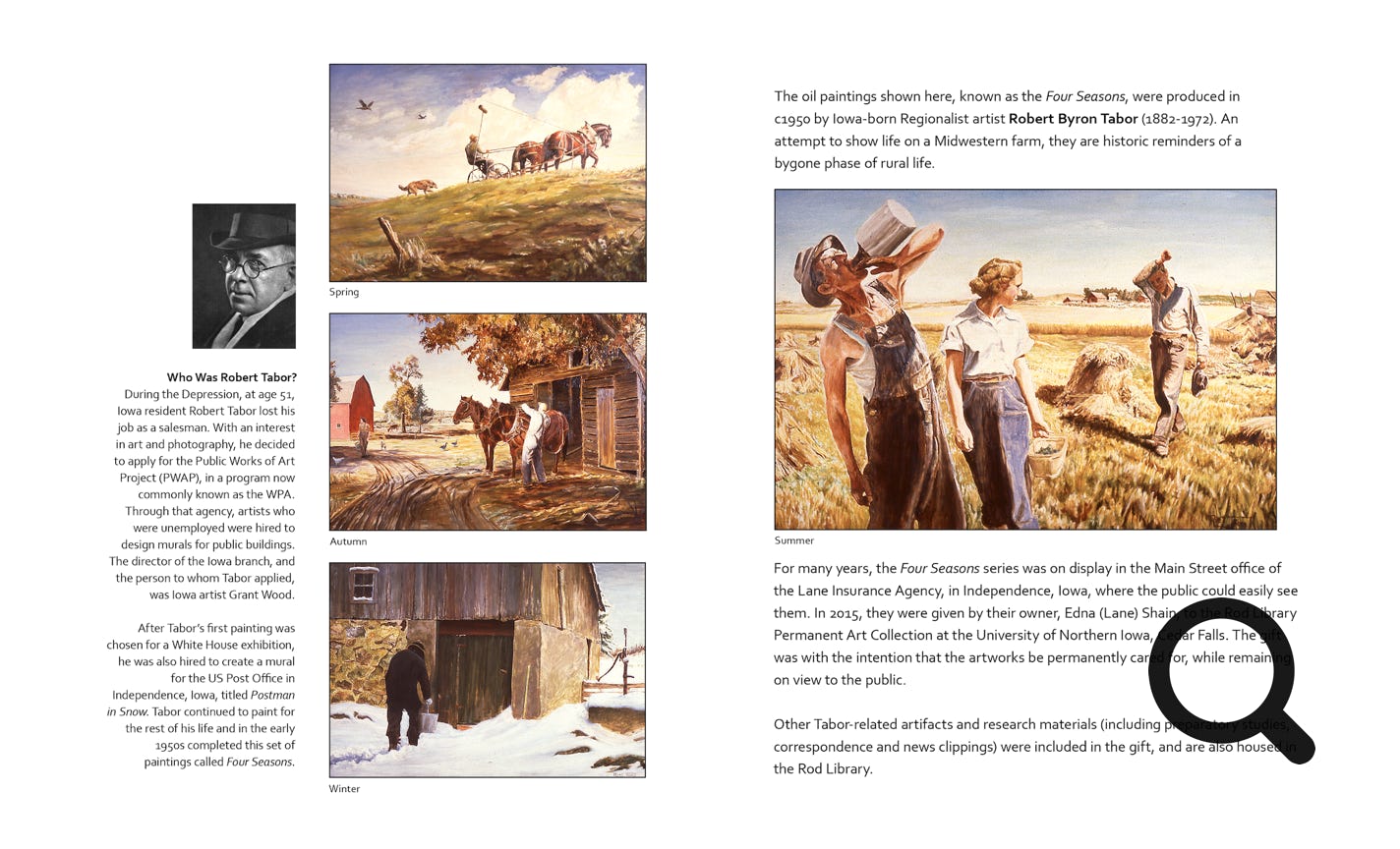

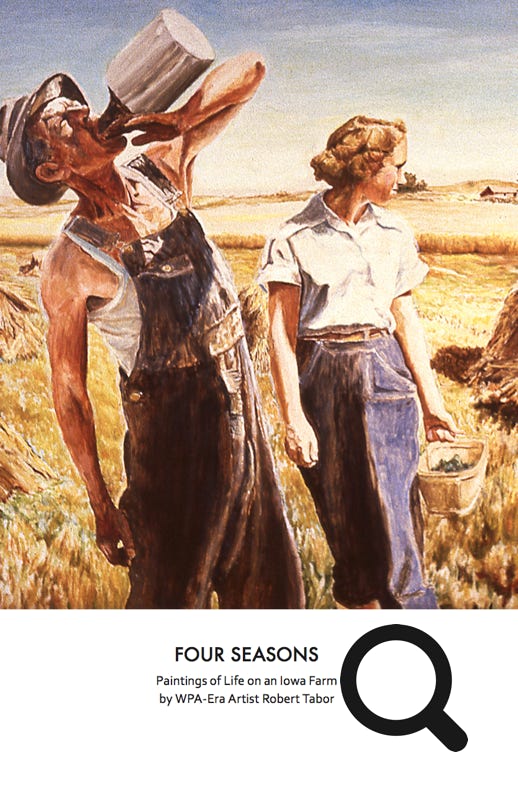

In the early 1950s, Tabor received his only major commission, aside from his earlier government work. Clark Swan, the owner of a local furniture store, offered Tabor $1,200 to create a series of paintings about aspects of life on an Iowa farm. Titled Four Seasons, these paintings, which were large compared to his earlier work, were exhibited for several years in the banquet room of the Hotel Pinicon in Independence. A few years later, they were acquired by the Lane Insurance Company for its office on Main Street, where they could be easily viewed from the street for many years. Owned for many years by the late Edna Lane Shain of Vinton, Iowa, these four Tabor paintings were given in 2014 to the Rod Library at the University of Northern Iowa, where they can now be viewed whenever the library is open.

In 1962, nearly thirty years after the Earth’s gravity had pulled his Winslow Homer down and propelled his life as an artist, Tabor offered to commemorate the discoveries of another Iowa-born adventurer, University of Iowa astrophysicist James Van Allen. After meeting with the celebrated scientist and three of his associates, Tabor worked from photographs (as he typically did) to reconstruct the “moment of discovery” in 1958 when that team had determined that the Earth is surrounded, outside its atmosphere, by what would thereafter be known as the Van Allen radiation belts.

Robert Tabor died at age 90, in 1972. Throughout his later life, there was never a shortage of local acclaim for his artistic achievements in Independence and Oelwein, Iowa, and in Olathe and Kiowa, Kansas, where he lived out his final years with his two daughters.

Looking back, it is sad albeit inevitable that while Vendue was Tabor’s earliest effort, it may also have been his crowning achievement. Swept along ever so briefly on the coattails of American Regionalism, his best work was never the equal of that of Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton. As the interest in Regionalism faded among art critics and collectors, so did Tabor’s fleeting dream of national prominence.

Robert D. Leighninger—

"The agencies of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration had an enormous and largely unrecognized role in defining the public space we now use. In a short period of ten years, the Public Works Administration, the Works Progress Administration, and the Civilian Conservation Corps built facilities in practically every community in the country.”

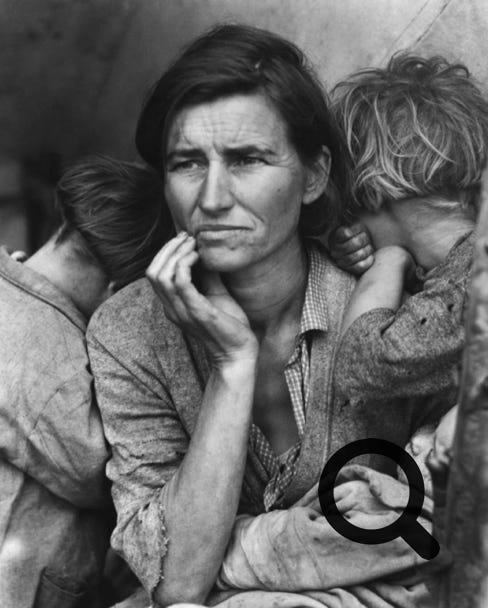

WPA photograph / Dorothea Lange

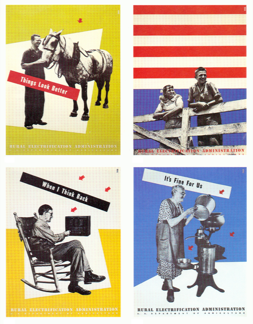

WPA government posters / various

Franklin D. Roosevelt—

“I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished…The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

Above Photograph of a Depression-era farm sale. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? (E.Y. Harburg and Jay Gomey)—

“They used to tell me I was

building a dream

With peace and glory ahead

Why should I be standing

in line

Just waiting for bread?

Once I built a railroad, I made it run

Made it race against time

Once I built a railroad, now

it's done

Brother, can you spare a dime?

Once I built a tower up to

the sun

Brick and rivet and lime

Once I built a tower, now

it's done

Brother, can you spare a dime?”

Left As part of the WPA program, Robert Tabor was commissioned to create this painting for the US Post Office in Independence IA.

Below Tabor’s painting, titled Main Street, of “the bank corner” at the intersection of Main Street and Highway 150 in Independence. Collection of the Independence Public Library.

Left and below

In October 2015, a reception was held at the Rod Library at the University of Northern Iowa for the formal installation of Tabor’s Four Seasons. They are now on permanent display on the bottom floor of the library, adjacent to the UNI Museum. They are open for public viewing during normal library hours.