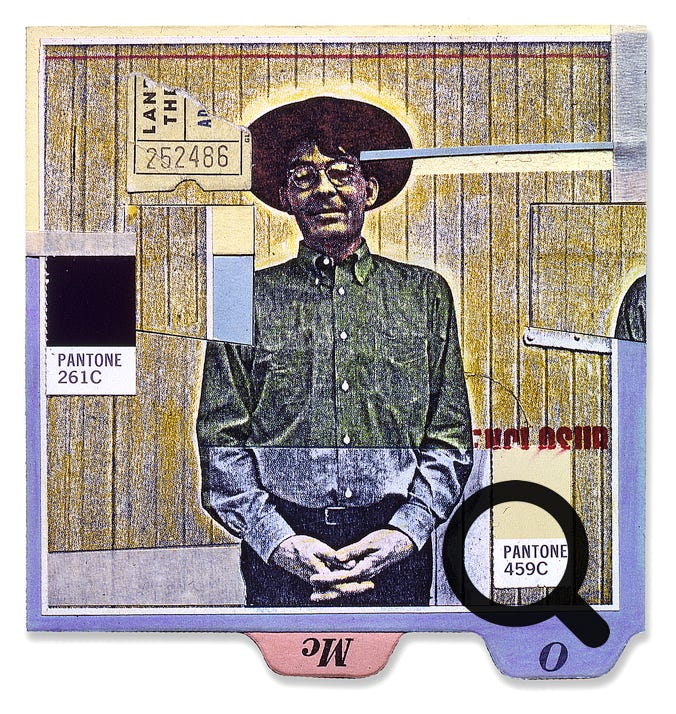

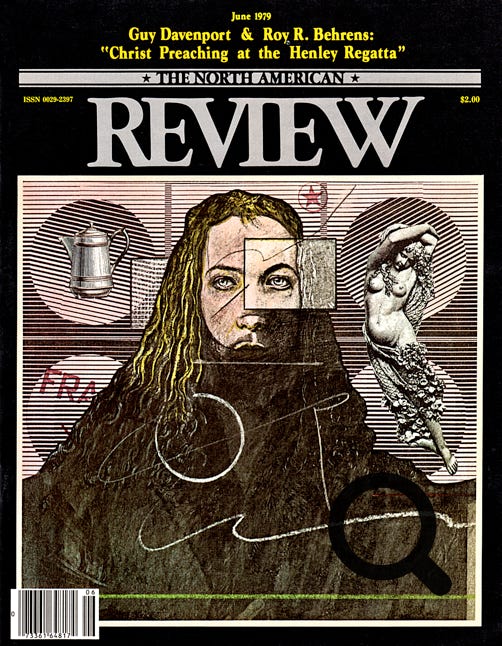

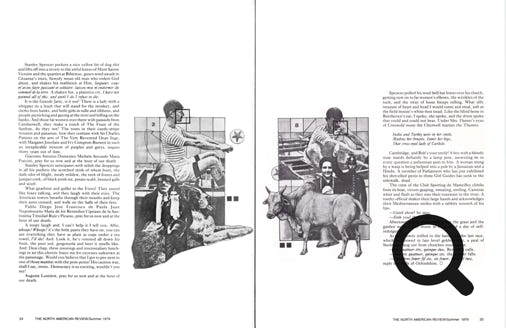

Roy R. Behrens Collage Portrait of Guy Davenport. Watercolor, colored pencil, collage and rubber stamp, c1979. Based on a photograph by Jonathan Williams.

Comte de

Lautréamont

As beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.

Max Ernst

Creativity is the capacity to grasp mutual distinct realities and to draw a spark from their juxtaposition.

Hugh Kenner

He [Guy Davenport] is the best explicator of the arts alive, because he assumes that the artists—painters, poets, describers of natural wonders—have the sort of mind he has: quick, unpredictable, alert for gaps to traverse toward unexpected terminus.

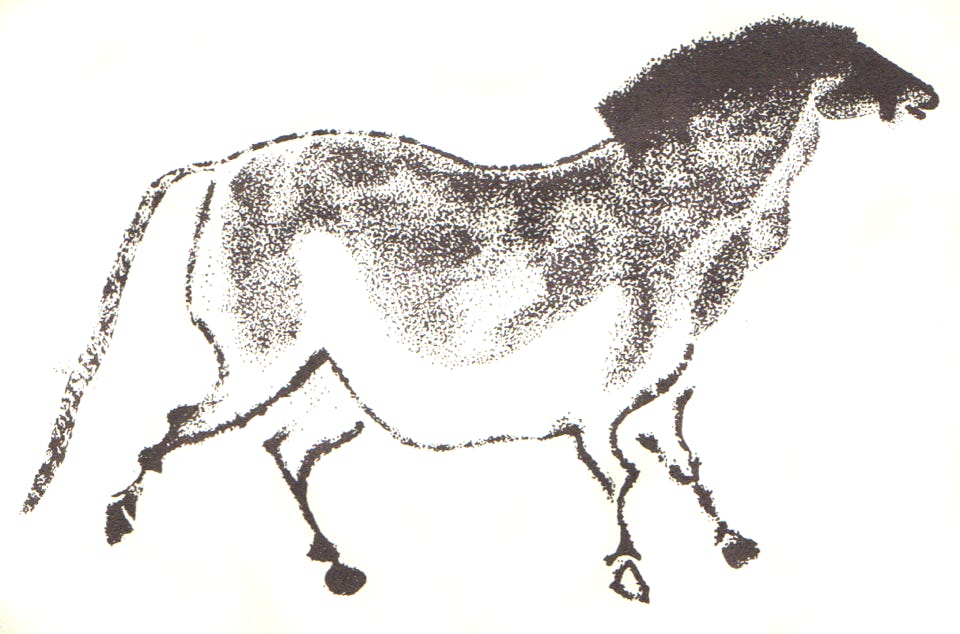

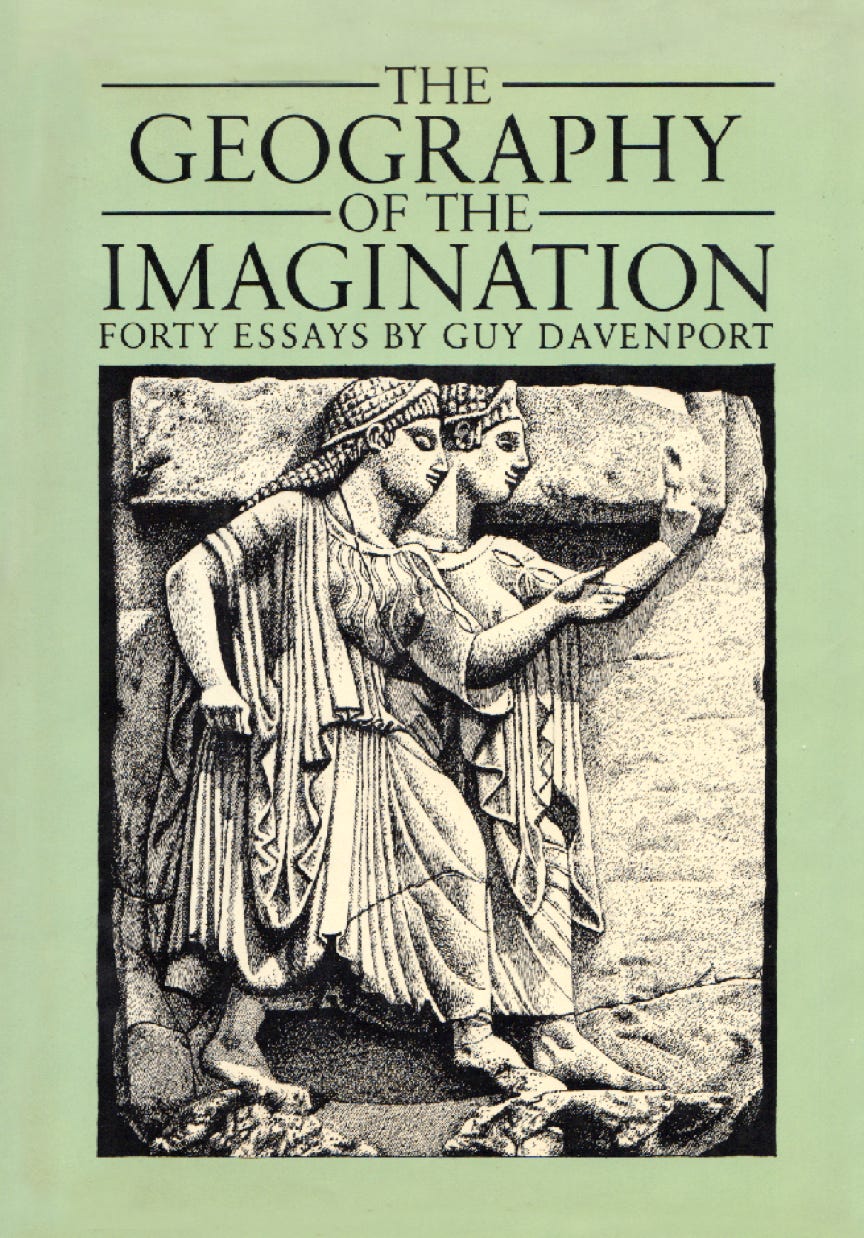

Examples of Davenport’s pen-and-ink illustrations, made by stippling. Above right is his rendition of the famous “Chinese horse” in the prehistoric Lascaux Cave. Below right is his drawing on the cover of what many regard as his finest book of essays.

Guy Davenport

The difference between the Parthenon and the World Trade Center, between a French wine glass and a German beer mug, between Bach and John Philip Sousa, between a bicycle and a horse, though explicable by historical moment, necessity, and destiny, is before all a difference of imagination.

Guy Davenport

Once, praising J.R.R. Tolkien to his friend Hugo Dyson, I was surprised to hear Dyson say that Tolkien would be a much better writer if he “hadn’t made it all up.”

Eudora Welty

James Joyce

In the name of Annah the Allmaziful, the Everliving, the Bringer of Plurabilities, haloed be her eve, her singtime sung, her rill be run, unhemmed as it is uneven!

Ezra Pound

Guy Davenport

The farmer and his wife [in Grant Wood’s American Gothic] are attended by symbols, she by two plants on the porch, a potted geranium and sansevieria, both tropical and alien to Iowa; he by the three-tined American pitchfork whose triune shape is repeated throughout the painting, in the bib of the overalls, the windows, the faces, the siding of the house, to give it a formal organization of impeccable harmony.

John Aubrey

I know of men aged forty or more who, whenever anything troubles them, dream they are back under the tyranny of their school master, so strong an impression does the horror of discipline leave.

• • •

SCUOLA DI

A designer

remembers

the writer

Guy Davenport

This memoir was posted originally (with somewhat different wording) on the Design Observer web blog at designobserver.com

on May 26, 2005. A printed version was also published in Ballast Quarterly Review, Vol 20 No 3 (Spring 2005), pp. 3-9, online here.

It seems I can no longer locate the carbon copy of my first letter to

Guy Davenport—the American essayist, fiction writer, poet, translator, painter, illustrator, university scholar, and a recipient in 1992 of a “genius award” from the MacArthur Foundation—who died of lung cancer on January 4, 2005, at age 77.

But I do have his very first answer to me, written (as its elegant typewritten heading reveals) on the birthday of Oswald Spengler on May 29, 1978. That was 27 years ago [about 42 years ago, as of this update], which means that Guy was fifty and a Distinguished Professor at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, while I was only 32 and teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. At the time, I was only remotely aware of his books and essays.

However, I had read his essay called “Post-Modern and After” in The Hudson Review (Spring 1978, pp. 229-240), which includes his mixed reactions to The Life of Fiction (1976), a book that I had co-produced with a University of Northern Iowa colleague, literary scholar Jerome Klinkowitz.

Our book’s text consisted of comments by Klinkowitz, intermixed with snatches from the writers of “postmodern” fiction (e.g., Hunter S. Thompson, Russell Banks, Kurt Vonnegut, and Gilbert Sorentino). At some point, the typescript was given to me, and I then made collages (dozens of them) to “antagonize” the text, and designed the layout for the book.

But the latter I did so ineptly that I still flinch when I think about it—much less do I like to revisit the scene. I was all but completely oblivious then to the most critical aspects of typography and page design, so Guy was entirely right to complain in his essay that the book was “printed in blinding Telephone Book sans serif, with the lines twice as long as the one you are now reading (so that losing one’s place at line’s end adds to the frustration of paying attention to a text that has the organization of a vaudevillian’s scrapbook of notices and billings).”

Ouch! I surely felt a jolt of pain when I first read that. But in the very next sentence, he not only restored my self-esteem, he elevated it: “Were it not for Roy Behrens’ splendid collages,” he wrote, “(scuola di Max Ernst and worthy of that master), one would zing the book across the room as an impertinence, the equivalent of a mumbling lecturer who is having rough going with his notes.”

In the face of such exuberance, how could I not respond to him? So I promptly sent what he later described as a “good-natured” letter, confessing that I alone (not Jerry K.) was to blame for both the abysmal typography (and the estimable images) in The Life of Fiction, and asked him what he meant by the phrase “scuola di Max Ernst.” As he explained, scuola di is art historian jargon for “school of” or “in the manner of”—although, he quickly added, “you’re not a copycat. It’s as if you learned everything in Ernst and put it behind you (or inside you) and took the next steps.”

A few years later, he titled one of his essays “Ernst Mach Max Ernst.” At all times in his letters, he had an irrepressible wit, by which I don’t mean humor (although he was wonderfully funny at times), but rather a gift for perceiving the most enlightening patterns. Indeed, whenever I think of him now, it almost always brings to mind a passage from Principles of Psychology in which William James remarked that “some people are far more sensitive to resemblances, and far more ready to point out wherein they consist, than others are. They are the wits, the poets, the inventors, the scientific men, the practical geniuses. A native talent for perceiving analogies is reckoned…as the leading fact in genius in every order.”

As for Davenport’s rate of production, according to an updated bibliography, at the time of his death he was the sole author or translator of exactly fifty books (including pamphlets published by small presses), the first of which was published in 1963. But that does not begin to account for his hundreds of published articles and book reviews in a wide range of magazines (e.g., The New Criterion, Harper’s, Hudson Review), his inclusion in anthologies, and the essays that he was commissioned to write as parts of books by others.

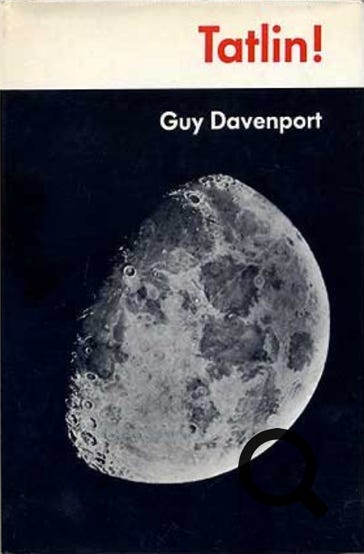

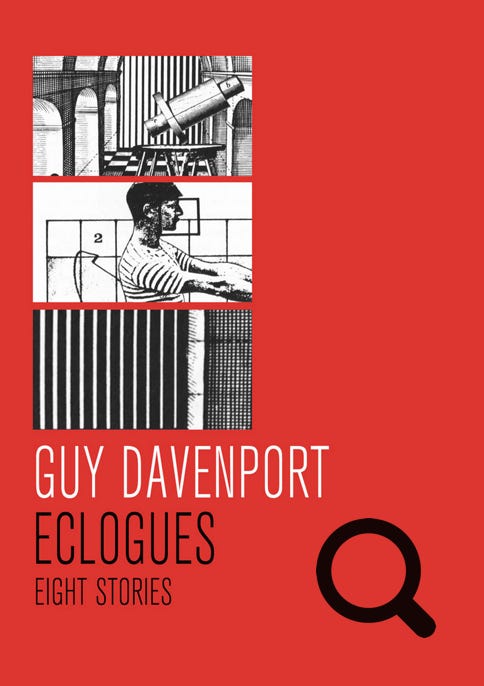

Early in his career, his primary reputation was for his translations of Greek poets and philosophers (e.g., Heraclitus, Diogenes, Sappho and Archilochus), many of which are available in Seven Greeks (1995). His first book of short stories was Tatlin! (1974), which was followed five years later by Da Vinci’s Bicycle (1979), then Eclogues (1981), Apples and Pears (1984), The Jules Verne Steam Balloon (1987), A Table of Green Fields (1993), The Cardiff Team (1996), and Twelve Stories (1997).

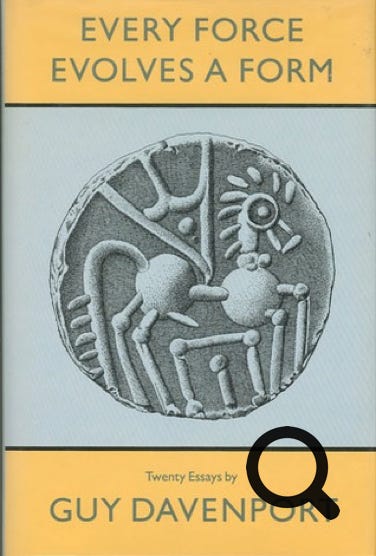

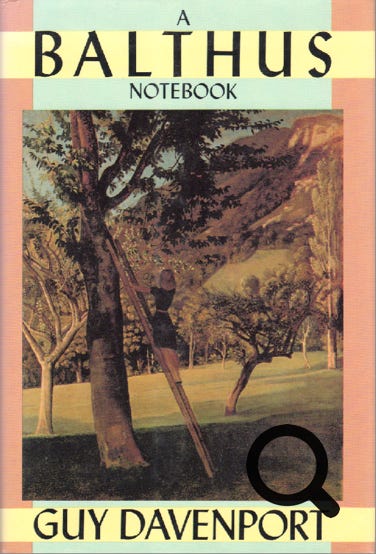

His collections of essays began with The Geography of the Imagination (1981), followed by Every Force Evolves a Form (1987), A Balthus Notebook (1989), The Hunter Gracchus and Other Papers on Literature and Art (1996), and Objects on a Table (1998). In The Death of Picasso (2003), a selection of stories and essays was culled from the full range of his writing life. Davenport, wrote George Steiner, “is among the very few truly original, truly autonomous voices now audible in American letters.”

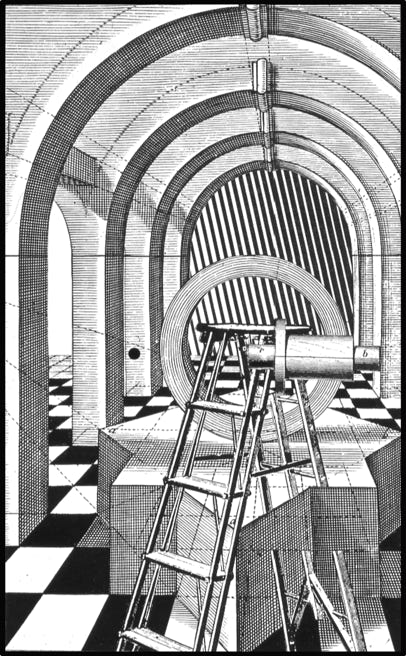

In addition to being a writer, Guy had drawn and painted since childhood (at age eleven, he had started an amateur newspaper in his hometown of Anderson, South Carolina, for which he wrote and also drew the pictures for all of the stories). As an adult, he used a crow quill pen to create the accompanying images for his own and the writings of others in which he nearly always used a tedious method called “stippling” (still infrequently used today in scientific illustration), which is sort of the “line art” equivalent of pointillism.

The day before he first wrote to me, Guy reported, he had labored for twelve hours on a stippled portrait of the composer Gioacchino Rossini (one square inch per hour, he claimed). Only recently had he taken up collage, using “locomotives, cars, stamps, and things with lettering picked up on the street (and out of the laundry).” And, he added, it had been my collages in The Life of Fiction that had prompted him to try it out. It is evidence of his generosity, his sincerity and openness that he said in that very first letter to me: “I wish I could think of a way to collaborate with you”—and shortly after that, we did.

For more than a decade, Guy and I exchanged letters of a length of one or two pages, sometimes as often as weekly. I saved all his letters, with copies of nearly all of mine. To correspond with him for so many years was among the wisest things I’ve done. Yet in truth it was always exhausting, since the intensity of his letters was forever a woeful reminder that I was writing not simply to an ordinary person but to a remarkably talented man whose powers of observation were astonishing at least.

The muscles in my mind withstood a rigorous weekly workout throughout those years—in part because, being so junior to him, I felt as if I had to craft every sentence uncommon precision and vigor. In sum, he taught me how to write by writing regularly to him. Just as he said of my artworks that they were scuola di Max Ernst, I could hardly be more pleased today if someone would say of my writings that they were “scuola di Guy.”

With the arrival of each of his letters—and with my extended reading of them—he told me magnificent stories about Viktor Shklovsky, Thomas Merton, Marianne Moore, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Eudora Welty, Louis Zukofsky, Charles Olson, Vladimir Tatlin, Pavel Tchelitchew, Balthus, the Shakers, Stan Brakhage, John Aubrey, Louis Agassiz, Charles Fourier, Vladimir Nabokov, Michel de Montaigne, and countless others.

In one of his letters, he reflected on the time he spent at Merton College at Oxford University, where he wrote an early thesis on the work of James Joyce, and where one of his lackluster teachers had been a “mumbling and pedantic” J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Much later, having settled in Lexington, Davenport met an older Kentuckian who had also studied at Oxford, but a generation earlier, and had been a classmate of Tolkien. This fellow claimed he did not know of Tolkien’s celebrity as a writer, but he remembered that he had back then a preoccupation with Kentucky, and had repeatedly asked him to spell out such common Appalachian names as Barefoot, Boffin and Baggins.

I recall that Guy was also linked with the American poet Ezra Pound, whose writings had been of interest to me since high school. During World War II, Pound had lived in Italy, and had broadcast to U.S. soldiers numerous radio talks that were pro-Fascist and anti-Semitic. At war’s end, a half-crazed Pound was captured by the US Army and imprisoned in an open pen (somewhat like those that have since been used at Guantanamo Bay). Accused of treason, he was returned to the US, but instead of being tried, he was declared “mentally unfit,” and ordered to indefinite confinement at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Washington DC. He survived that Bosch-like limbo for a dozen years, until, in 1958 (at age 73), through the efforts of various writers (notably Archibald MacLeish), Pound was eventually discharged, and returned to live harmlessly (in silence and seclusion) in the mountains of Italy.

Davenport (whose Harvard doctoral projects concerned the Cantos of Pound) was a younger but active participant in the campaign to obtain Pound’s release. Guy told me in his letters that he visited Pound “fairly regularly for 6 years,” beginning in 1952, and that it was he who “did the footwork and paperwork that got Ez out, and [I] have his letter of gratitude in my files.”

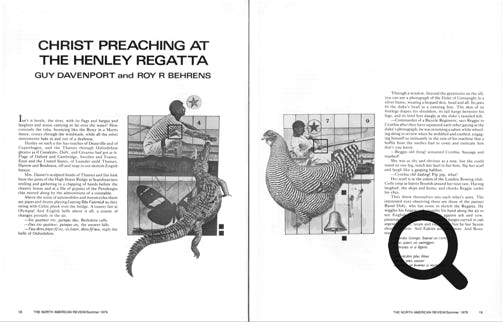

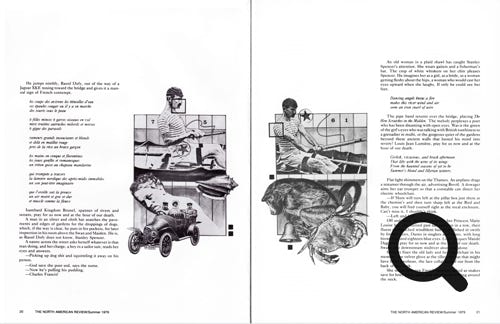

Beyond our letters, Guy and I collaborated on two very interesting projects. They were not essays, but experimental short stories, bewildering in their complexities, for which he did the writing while I made the illustrations. This all came about less than a year into our correspondence, and was triggered by Robley Wilson, then editor of the North American Review, who welcomed the opportunity to feature a multi-page illustrated story by Davenport and myself, along with a full-color cover.

A few months later Guy produced a story he had written with my work in mind. Titled “Christ Preaching at the Henley Regatta,” it was a tribute to the visionary British painter Stanley Spencer, who was born and raised in Cookham, a village on the River Thames. Guy’s title is a parody, since, when Spencer died in 1959, he was working on a painting (which remains unfinished) called Christ Preaching at the Cookham Regatta. It was typical of Spencer to portray an exalted and solemn event (such as the Sermon on the Mount) being held in a commonplace setting (such as an annual boat race on the banks of the river). Perhaps the most famous example of this is an earlier painting by Spencer, titled The Resurrection, Cookham (c1927), in which lots of local folk (neatly dressed with hair intact) are shown as bursting from their graves and briskly springing back to life.

I really had enormous fun while illustrating what Guy and I referred to in our letters as CPATHR. Given free rein on the layout, I extended the text of his story to take up eight full pages, with each page also playing host to one of eight collages. Looking back, I am now disappointed with nearly all the inside collages, but I still love the full-color cover (a burlesque of Albrecht Dürer’s famous self-portrait in which he resembles Christ). So did Guy: “Your Christus with Coffee Pot and Primavera,” he wrote, “is a grand piece of work.” Some time later, I suspect because of the story alone (and his growing celebrity), that first collaboration was chosen for inclusion in The Pushcart Prize VII: Best of the Small Presses (1982).

In the meantime, Guy and I marched on to the sounds of our differing drummers. He had plans to publish next, through North Point Press, a collection of his recent short stories, of which CPATHR would be one. Preserve the original artwork for the cover of the NAR, he implored, in case that story should become the title story of the book. But that did not happen. The title chosen for the book was Eclogues. But inside is CPATHR and its eight grayscale images—without, of course, the cover art.

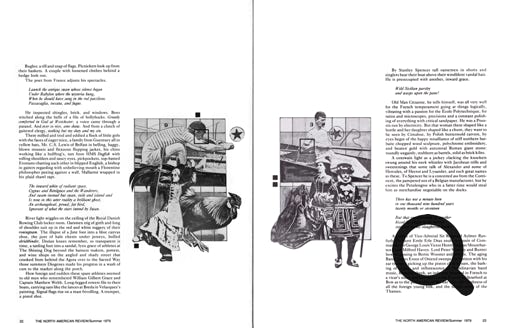

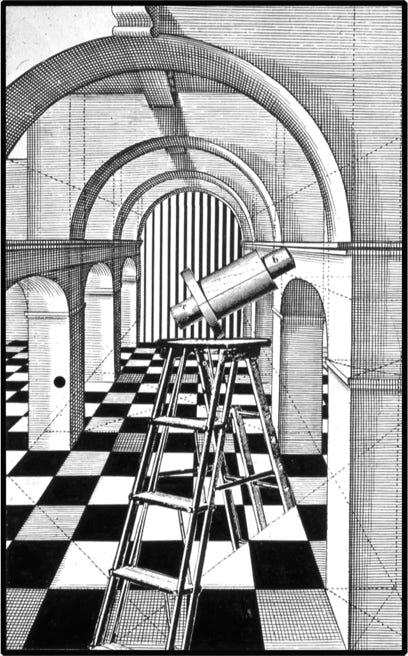

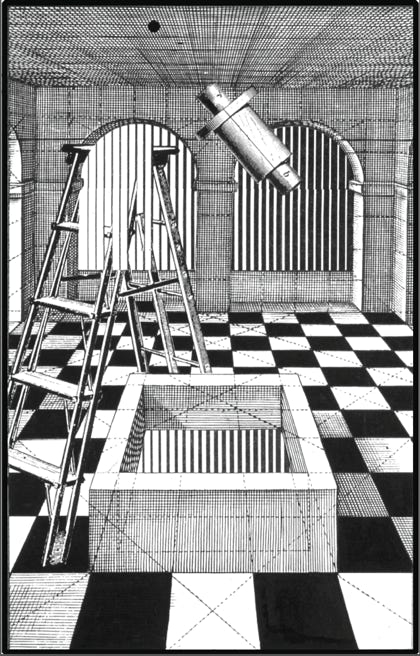

It also included our second collaboration, in which I again illustrated a new short story by Guy, this one featuring T.E. Hulme, the British literary critic, in the setting of Bologna at the closing of the first decade of the 20th Century (Hulme himself would later die during World War I). The title Guy gave to that story was “Lo Splendore della Luce at Bologna.”

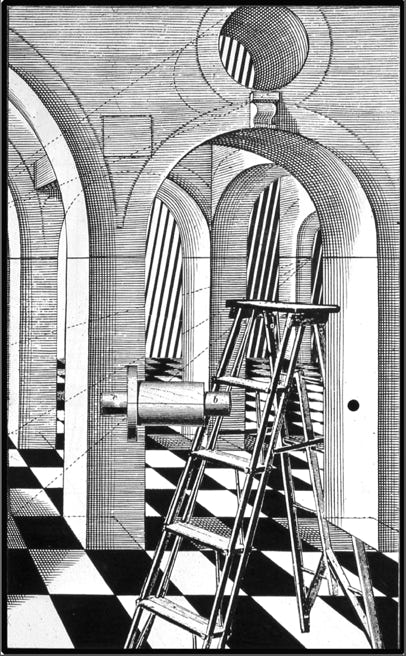

I doubt if I had heard of Hulme. And the more I read about him, the less ecstatic I became (not to mention the fact that my personal life was in a crisis state back then). As a result, our second collaboration was far more burdensome than the first. I simply could never identify with the story nor with its protagonist. Eventually, I solved it by producing four collages that, to my mind, were a “hard and dry” amalgam of empirical British philosophy and the Italian fascination with linear perspective. I still enjoy the illustrations (below), in the sense that they’re more or less clever, but they surely do not have the verve or the passion that I felt while working on CPATHR.

Today, if you look at a copy of Eclogues (and affordable copies are easily found, because it was later reissued by the Johns Hopkins University Press), you cannot help but notice that the book is dedicated “to Bonnie Jean.” She is Bonnie Jean Cox, who was Davenport’s loving companion for nearly forty years, and the person who shaped his memorial at the University of Kentucky on Saturday, May 8, 2005.

I myself was not in attendance that day. But according to an article in the Lexington Herald-Leader, it lasted about 90 minutes, and both began and ended with beautiful songs by the Shakers. “Every force evolves a form,” as Mother Ann Lee and Guy would say, so a sweet gum tree was named for him, and a cluster of his closest friends aired their fondest memories of “the Hermit of Lexington,” as Jonathan Williams once called him, or “Dav,” as Ezra Pound preferred.

Among those who spoke that day was Erik Anderson Reece, a former student of Davenport who authored A Balance of Quinces (1996), which may be the only book thus far about Guy as a visual artist. He recalled that after receiving that $365,000 genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation, whenever they would go to lunch, Guy would refuse to allow him to pay. He would invariably say instead, “Oh, let’s let John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur pay for it.”

Another speaker was Wendell Berry, the well-known essayist who taught at the University of Kentucky. He remembered that his and Guy’s offices were adjacent. “By walking a few steps and leaning on his doorjamb, and saying a word or two of greeting, I could start Guy decanting whatever happened to be on his mind,” said Berry. “But my metaphor is off. The flow started not from a decanter but from a stream, and somewhere upstream it was raining.”

• • •

Roy R. Behrens, dust jacket for The Life of Fiction (1977).

Publisher’s book promotion (1977).

Aristotle

The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor; it is the one thing that cannot be learned from others; and it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in dissimilars.

Covers from a small selection of his books.

Guy Davenport

The closest I have ever gotten to the secret and inner [J.R.R.] Tolkien was in casual conversation on a snowy day in Shelbyville, Kentucky. I forget how in the world we came to talk of Tolkien at all, but I began plying questions as soon as I knew that I was talking to a man who had been at Oxford as a classmate of Ronald Tolkien’s. He was a history teacher, Allen Barnett. He had never read The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. Indeed, he was astonished and pleased to know that his friend of so many years ago had made a name for himself as a writer.

“Imagine that! You know, he used to have the most extraordinary interest in people here in Kentucky. He could never get enough of my tales of Kentucky folk. He used to make me repeat family names like Barefoot and Boffin and Baggins and good country names like that.”

Left Photograph of James Joyce playing the guitar. Above Cover of a commemorative issue of Ballast Quarterly Review, published by the author at the time of Guy Davenport’s death.

C.G. Jung

[Joyce’s Ulysses] can just as well be read backwards, for it has no back and no front, no top and no bottom. Everything could easily have happened before, or might have happened afterwards. You can read any of the conversations just as pleasurably backwards, for you don’t miss the point of the gags. Every sentence is a gag, but taken together they make no point. You can also stop in the middle of a sentence—the first half still makes sense enough to live by itself, or at least seems to. The whole work has the character of a worm cut in half, that can grow a new head or a new tail as required.