IN THE MID-1950s, when I was a student in sixth grade, our class was asked to imagine how it would feel to travel to the moon. This was a dozen years prior to the first moon landing.

As a group, we designed a streamlined spaceship, a cigar-shaped Art Deco contraption that looked like the ill-conceived offspring of a firecracker and a yard dart. Individually, each student created a poster, built a model, or wrote a letter to parents and friends, reporting on what it was like to visit the moon. Wrote one classmate, “Our spaceship will travel seven miles a second, so we should be back home on earth in seven hours.”

I myself chose to write a poem, and the verse that I wrote for that project was featured in an article in my hometown newspaper. I suppose it was my first peer-reviewed publication of sorts. It went like this—

If we took a trip

To the moon

In a space ship

Very soon,

We’d reach the moon at noon

Or three hours more,

Then onto the moon

Our ship would soar.

The moon is a very queer place

Floating around in

The middle of space.

The man in the moon

Is only black streaks.

The moon has no people,

As Mars has freaks.

I was eleven when I wrote that. I don’t recall anyone talking about meter or rhythm or rhyme, yet I was well aware of these, if only because I had witnessed them in the writings of others.

Aside from popular song lyrics (“There’s n-o-o business like sh-o-o-w business” or “Bebop-a-loo-lah, she’s my baby, bebop-a-loo-lah, I don’t mean maybe”), I was acquainted with rhythmic speech patterns in the King James Version of the Bible (The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want) and I would eventually realize (as have countless others) that the cadence of its verses had, in the words of Eudora Welty, “entered our ears and our memories for good. The evidence, or the ghost of it, lingers in all our books.”

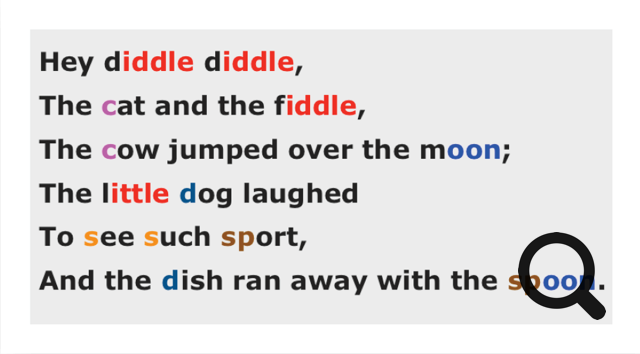

Even more enduring, I think, was my familiarity with nursery rhymes, and especially my favorite, called “Hey Diddle Diddle,” which is now typically classified as nonsense verse—

Hey, diddle, diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon;

The little dog laughed

To see such sport,

And the dish ran away with the spoon.

Reverie, fantasy, surrealist conceit, the content of a daydream, yes—but it is anything but nonsense. Rather, it is artfully crafted linguistic design, an exemplar of speech at its finest.

There is, for example, an echo between diddle, fiddle and little (double syllable end rhyme, technically

known as “feminine rhyme”), and between moon and spoon (single syllable end rhyme, called “masculine rhyme”). And of course there are also alliterative links between cat and cow, little and laughed, see and such,

and sport and spoon.

In the first published version of this nursery rhyme (which dates from 1765), the fifth line was “To see such craft,” so that laughed and craft were also rhymed, and the pattern of similar lines was AABCCB instead of (as I learned it) AABCDB.

As for the poem’s subject matter, it may not be unfair to note that (at least when I was growing up) fiddle strings were made from catgut, cheese was obtained from the milk of a cow, the moon was made of green cheese, the crescent moon (the standard shape on outhouse doors) was the same as the shape of a cow’s horn, and moon was a vocal reminder of moo.

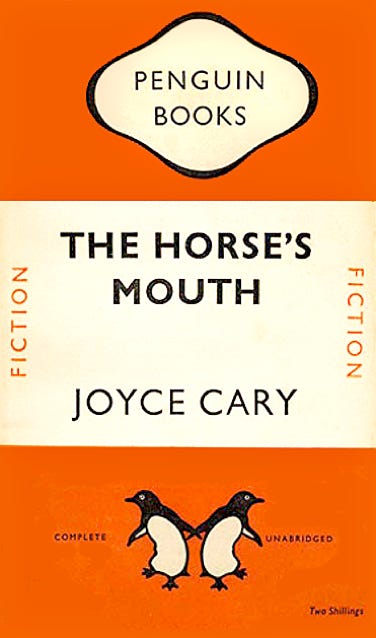

I love to read “Hey Diddle Diddle” aloud. Like prose intended for the voice, it is not designed for skimming or speed-reading. Evocative prose has the same rhythmic exactness as verse, regardless of whether it has any rhymes, as in for example the opening lines of The Horse’s Mouth by Joyce Cary—

I was walking by the Thames. Half-past morning on an

autumn day. Sun in a mist. Like an orange in a fried fish

shop. All bright below. Low tide, dusty water and a crooked bar of straw, chicken-boxes, dirt and oil from mud to mud. Like a viper swimming in skim milk. The old serpent, symbol of nature and love.

Or, as in this equally wonderful paragraph from the autobiography of Eudora Welty, One Writer’s Beginning—

At around age six, perhaps, I was standing by myself in our front yard waiting for supper, just at that hour in a late summer day when the sun is already below the horizon and the risen full moon in the visible sky stops being chalky and begins to take on light. There comes the moment, and I saw it then, when the moon goes from flat to round. For the first time it met my eyes as a globe. The word “moon” came into my mouth as though fed to me out of a silver spoon. Held in my mouth, the moon became a word. It had the roundness of a Concord grape Grandpa took off his vine and gave me to suck out of its skin and swallow whole, in Ohio.

I STILL CLEARLY remember the day when I met James and Meryl Hearst for the first time.

I remember it in part because I have a photograph of it. It took place during my freshman year at UNI. I was an art student, and I had just returned to Iowa from a summer in California, where I had studied pottery with a person who had been among the first women students at the Weimar Bauhaus. The Department of Art hosted an on-campus party in which non-art members of the faculty were invited to a gathering at the ceramics studio quonset hut, where they painted their designs on greenware pots that had been wheel-thrown by the students.

In that one surviving photo, I am quietly standing beside music professor Don Wendt and Meryl Hearst. James Hearst is not in the photo, but he was nearby in his wheel chair. I remember how puzzled I was that day by the child-like quality of his art.

That day, I didn’t talk to Jim and Meryl. I was shy, because for years I’d known about him as a celebrated Iowa poet. I had grown up about thirty miles from Cedar Falls, and had often frequently read about him in the newspaper. I had seen the reports about Carl Sandburg’s visit to the UNI campus in 1963, when I was a junior in high school, with a photo of the Hearsts beside that celebrated, if controversial, Socialist.

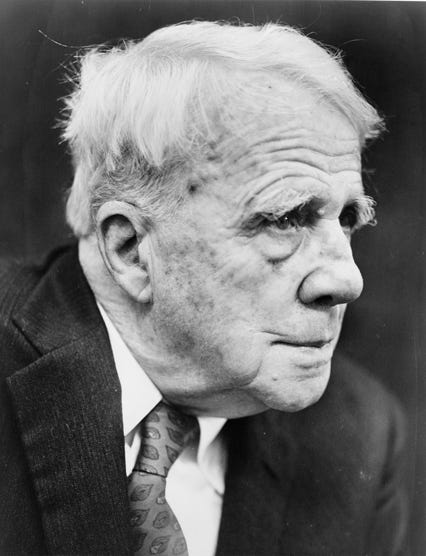

I had also studied Hearst’s and Sandburg’s poetry in a high school literature class, along with that of Robert Frost, who had visited UNI in 1940, and who, to my boundless enjoyment, had been chosen by John F. Kennedy to read aloud a poem at the presidential inauguration in 1961. I was so proud of my country (I cannot say the same today) as I witnessed Frost’s attempt to read, despite the blinding overhead sun, annoying wind, and—believe it or not—a fire in the podium. Undaunted, the frail and aging Robert Frost put down the paper and finished the recitation from memory.

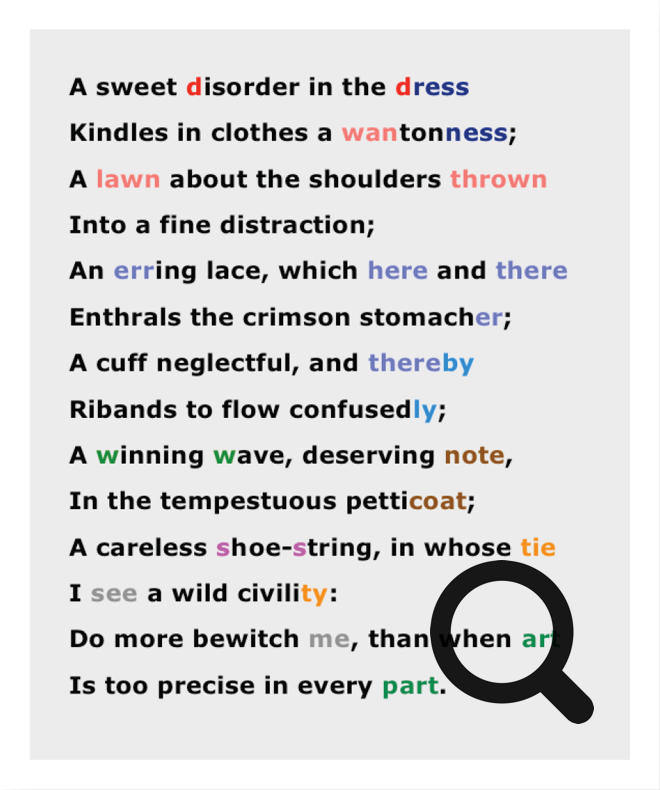

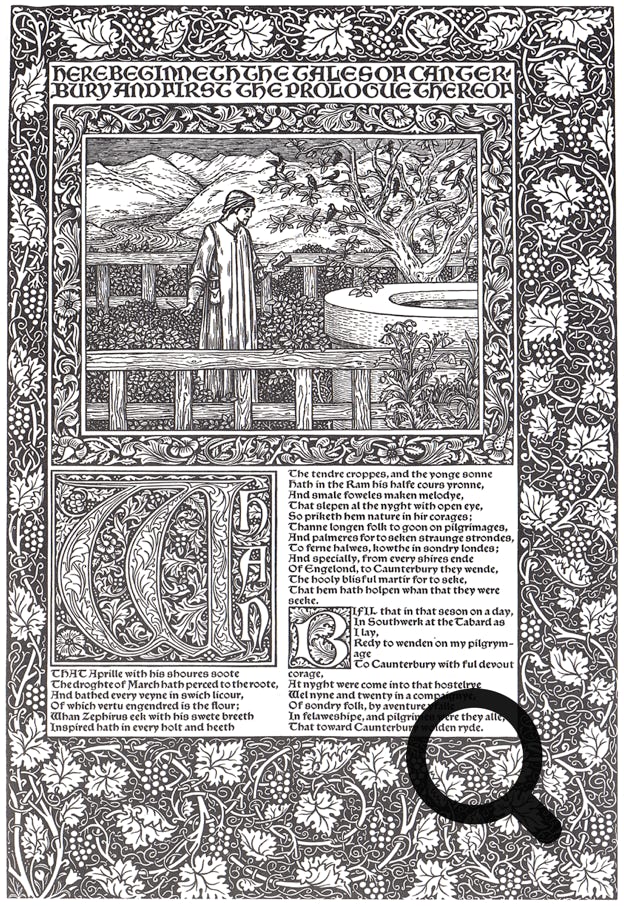

My high school speech, theatre and literature teacher (her name was Florence Helt) had been an important influence on me, as she was on other students as well. She was a stalwart defender of Sandburg’s controversial “free verse,” a practice Frost had likened to “playing tennis without a net.” Among other things, she required that we memorize the first 15 or so lines of Chaucer’s prologue to The Canterbury Tales, in the English in which they were written. Here are the first six lines—

Whan that aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of march hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour,

Whan zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth…

When I entered UNI as a freshman art student in the fall of 1964, I soon discovered that, because of my fondness for literature, nearly all my lasting friends would be not visual artists but writers and actors, often a year or two older, whether prose writers, poets or playwrights. They had read the same authors that I had, they loved wit and repartée, and our discussions were often hilarious when we gathered almost nightly for far too much black coffee at the Pizza House, at the foot of the College Hill, sometimes until three in the morning. In addition, many of them were or had been students of James Hearst.

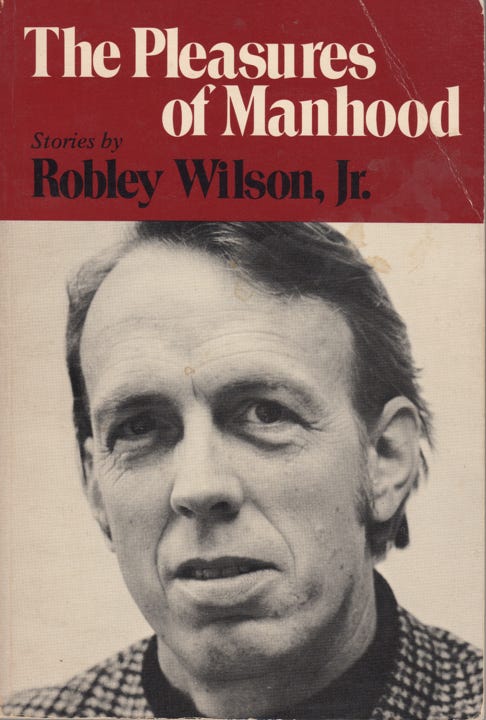

I was never a student of Hearst, but I overheard conversations about what they had gained from his teaching. Later, I took one course in poetry, but my teacher was a recently-arrived younger member of the faculty, a fiction writer and poet named Robley Wilson.

My friends were Wilson’s students too, and I recall a particular evening in which a small group of us were having coffee when Robley joined our table. I remember our delight when he said that he believed that Bob Dylan was not only a folk singer—he was also a genuine poet. What? A folk singer could be a serious poet? We couldn’t be more pleased. It was a game-changing moment for us, if one that feels more or less trivial now.

It may have been around that time that Jim Hearst gave a public talk about creative writing, which took place in the basement of his home, which is now the Hearst Center for the Arts. My friends and I were in the audience. My memory of his talk is faint, but a single moment still stands out. At some point, he quoted American poet Marianne Moore as having defined poetry as “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.”

I RECEIVED MY undergraduate degree in May of 1968, then spent the summer in Aspen, Colorado. I was a painting assistant at a school of contemporary art where James Hearst had taught a summer poetry course for a number of years. I recall an afternoon I spent at the Hearst home in Aspen. We all sat facing a large window. As was characteristic of Jim, we didn’t talk about poetry or art. We talked about hummingbirds, dozens of which were feeding at close range in the window.

Sitting with us that afternoon was a man I had not met before. He was a writer and the head of the Humanities Program at the San Francisco Art Institute. He too was teaching in Aspen, and his name was Kenneth Lash. I would not have imagined it then, but a few years later, Lash would become the Head of the UNI Department of Art. In the years that followed Aspen, I taught high school until I was drafted out of the classroom, was diverted to the US Marine Corps, and afterwards earned a graduate degree at the Rhode Island School of Design.

As soon as I had completed graduate school, Lash (recalling our meeting in Aspen) invited me to return temporarily to UNI to replace a full-time teacher who had unexpectedly become ill. Shortly after I moved back to Cedar Falls, Lash received a reprimand from the UNI administration for a public poetic infraction: At the time, there was an outspoken conservative state senator in Iowa named Francis Messerly, whose views were especially offensive. Lash made the naïve mistake of submitting a letter to the editor (in the student newspaper? or was it in the Waterloo Courier?) which simply read:

Each time I hear of Messerly,

I like him less and lesserly.

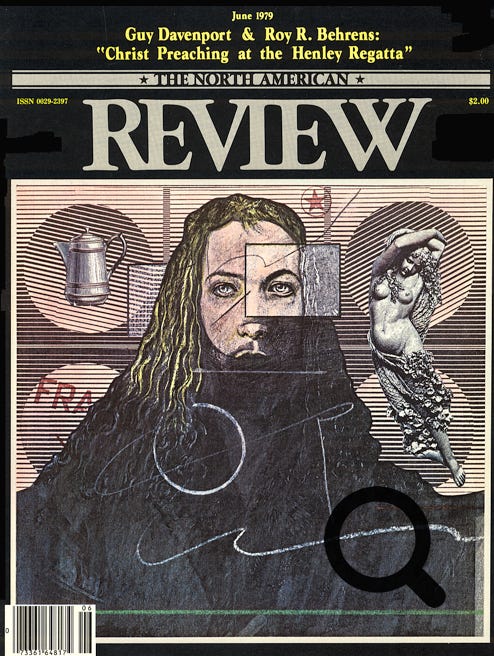

In the meantime, Lash, Jim Hearst and Robley Wilson, all teaching at UNI in the early 1970s, had increasingly grown to be friends. In 1969, Wilson had succeeded in moving the ownership of the North American Review from Coe College (where poet Robert Dana had resumed its publication in 1964) to UNI. Founded in Boston in 1815, the NAR was the oldest literary magazine in the country, but it had decidedly crashed and burned in 1940 when its owner at the time was accused of spying for the Japanese.

While it was Dana who revived the NAR, it was Robley Wilson who restored it all but single-handedly to national prominence as a leading literary magazine. Looking back, the scope and swiftness of his achievement is simply unbelievable: Between 1969 and 2000 (when he retired as editor), the NAR was twice the recipient of the National Magazine Award for Fiction (beating out the New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, Esquire and other famous magazines); was a finalist for the same award five additional years; had nine pieces chosen for the Pushcart Prize; and was regularly included in any number of major literary anthologies, among them the Best American Short Stories, Best American Sports Writing and Best American Travel Writing.

In the fall of 1974, a special issue of the NAR was devoted to the life and work of James Hearst. Ken Lash was the guest editor, and, having begun to participate in the magazine’s art direction, I was involved in the issue’s design. I left the university in 1976 to teach at other schools, but I continued to be associated with the NAR, even from a distance, and then again directly when I rejoined the UNI art faculty in 1990.

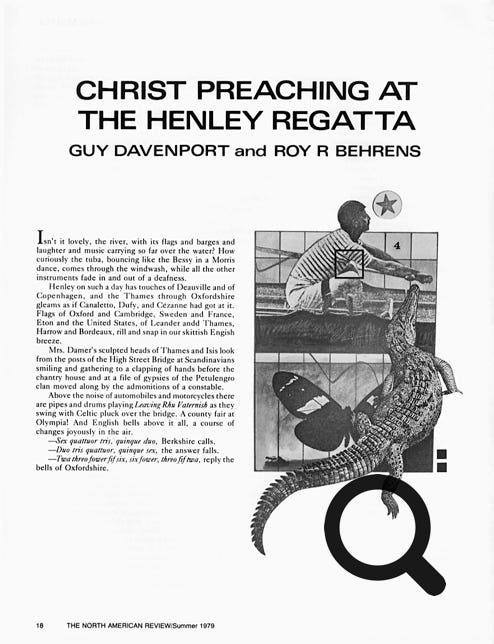

For me, one of the high points in all of those years took place in 1979, while I was teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. By exchanging letters, I had become friends with the writer Guy Davenport, and when he and I collaborated on an illustrated short story, titled “Christ Preaching at the Henley Regatta,” it was published in the NAR (along with a cover that I had designed), and was chosen for the Pushcart Prize.

While still living in Milwaukee, I was contracted in 1984 by Prentice-Hall to write a textbook for first-year students of art and design. The title of the published book was Design in the Visual Arts. It consisted of three major sections, the third of which was focused on the use of metaphor, in language and in visual art. As I planned that section, it occurred to me that I should share with young artists and designers what I had learned from the poetry of James Hearst. I wrote to Jim, asking for permission to reprint a well-known poem of his called “Truth”—

How the devil do I know

If there are rocks in your field,

Plow it and find out.

If the plow strikes something

harder than earth, the point

shatters at a sudden blow

and the tractor jerks sidewise

and dumps you off your seat—

because the spring hitch

isn’t set to trip quickly enough

and it never is—probably

you hit a rock. That means

the glacier emptied his pocket

in your field as well as mine,

but the connection with a thing

is the only truth I know of,

so plow it.

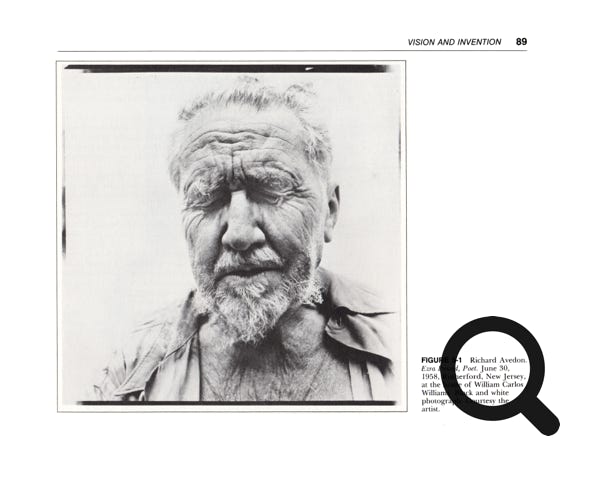

At the same time, I also sent a letter to Richard Avedon, the New York photographer. I asked permission to include his portrait photograph of the poet Ezra Pound. Soon after, I received a call in my office from his assistant, who asked how much I was willing to pay. She mentioned that the usual rate for one-time use was around $5000. That was probably ten times the permissions allotment allowed for the ewhole book. In that case, his assistant said, could I send a letter to Mr. Avedon, explaining how I would use the photograph and why it was important? I did that, and soon after I received permission and a bill for about $50.

In that book, this is the context in which I referred to Avedon’s portrait of Ezra Pound, made in 1958 at the home of William Carlos Williams. This is what I wrote—

My most vivid encounter with metaphor began when I was very young. There was a drainage ditch on the south edge of my parents’ property, and around the ditch grew waist-high weeds. Stalking slowly by the ditch, I would focus on the weeds, hoping to catch grasshoppers with my bare hands. Often when I did this, I would be indirectly aware of a tiny streak of brown or gray darting on the ground below. It was of course a field mouse. But it moved so quickly that no matter when I switched my gaze, it would no longer be there. It was like looking at faint stars, which are visible when you look aside but almost disappear when you look at them directly. It was as if the mouse was there, and yet it wasn’t. It did not even move the grass.

A few years after that childhood experience, when I was twelve years old, I repeatedly noticed a series of brief newspaper items in the Des Moines Register, about the release from a mental institution of a man named Ezra Pound. With each news item, there was a portrait photograph (always the same photograph) of, as the paper described him, this American poet who had been declared a traitor in World War II. Gradually, I learned of course that Pound had broadcast subversive (and anti-semitic) radio talks in Mussolini’s Italy. At war’s end, he had been captured by the US Army, returned to Washington, and was committed indefinitely to St Elizabeth’s Hospital for the Insane. I also learned that Ezra Pound was one of the greatest poets of the century. But initially when I saw his face, I only focused on his painful expression, and mused about his curious name—a man whose name was a

unit of measurement.

Many years after all this, when I was more than twenty-three, I found myself lost and despondent, strolling aimlessly at night on an American naval base. Somehow, having finished college and having taught high school for nearly a year, I had been drafted out of the classroom and sent to the US Marine Corps. With nearly two years of service ahead, I thought of all the meaningful things I would rather be doing—I could be traveling, writing

books, teaching, or inventing things. I could even be writing poetry.

As I walked, I wandered into the base library, and looked for a book that might offer relief. To my surprise, I found a book of poetry by Ezra Pound. And when I opened the pages, I saw these astonishing lines—

And the days are not full enough

And the nights are not full enough

And life slips by like a field mouse

Not shaking the grass.

AS A METAPHORIC full stop, I want to conclude with an additional poem by James Hearst. It was written in 1979 when he was almost eighty years old. It’s about what happened years before, in 1923, when his brother, Robert Russell Hearst, who was two years younger than Jim, died of lymphoma when he (his brother) was only twenty-one. As poetry can do so well, it both relives and enlivens the mournful loss by imagining his brother’s death as a childhood game of hide and seek in a cornfield. Titled

“End of the Game,” it reads like this—

Two little boys dusty with pollen

would need clean faces to come

to the supper table. In the

cornfield we hid from each other,

racing up and down the rows like

rabbits, you always gave yourself

away with a snort of laughter.

It is your turn to hide while

I cover my eyes. I hear the rustle

And murmur of leaves drying in

the warm October sun. But now you

are quiet and I cannot find you.

Come out, brother, come out,

I am afraid. Soon it will be dark

And mother will scold us if

we are late for supper.

• • •