in the eye

of the beholder

The James Lechay

Portrait Controversy

at the University of

Northern Iowa

This essay was published initially in Tractor: Iowa Arts and Culture (Cedar Rapids IA), 1999. Copyright © by Roy R. Behrens.

in the eye

of the beholder

The James Lechay

Portrait Controversy

at the University of

Northern Iowa

This essay was published initially in Tractor: Iowa Arts and Culture (Cedar Rapids IA), 1999. Copyright © by Roy R. Behrens.

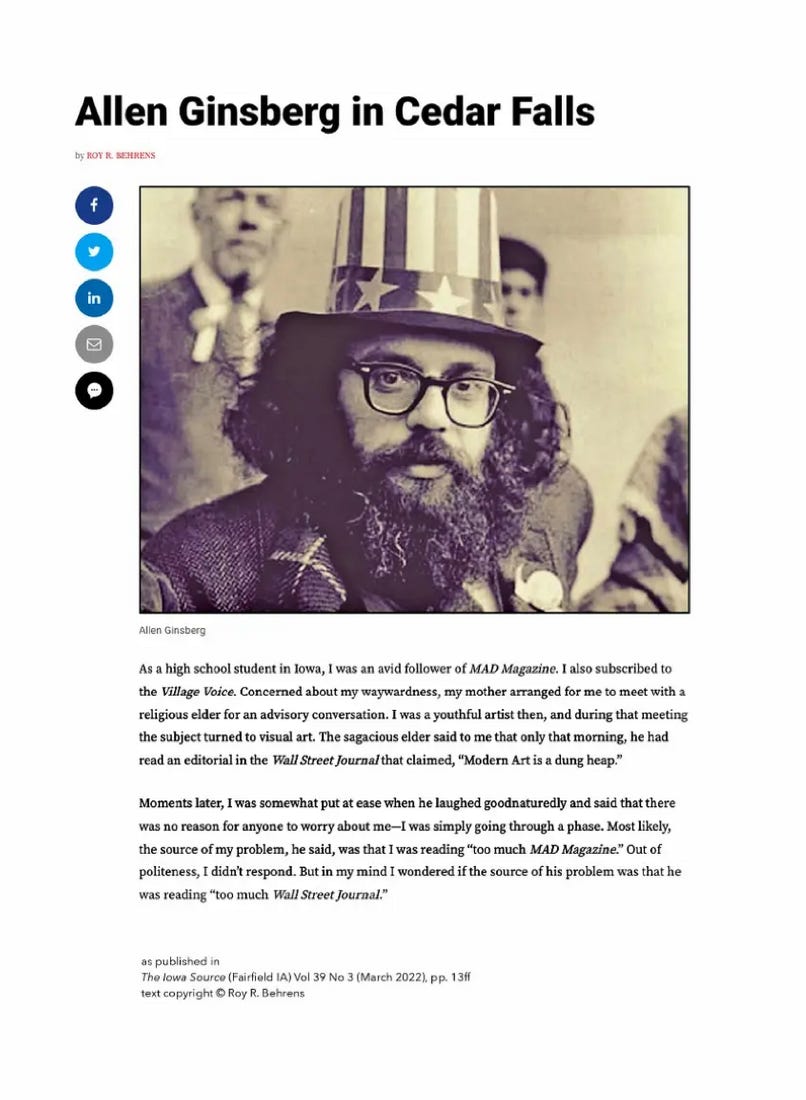

Above James Lechay, Portrait of J.W. Maucker (1966). Oil on canvas, 40”w x 49”h. Permanent Art Collection, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls.

IN 1941, WHEN New York painter James Lechay was 34, one of his paintings was awarded third prize in the prestigious American Painting Competition at the Art Institute of Chicago, which also purchased it. Artist Ivan Albright (Madeleine Albright’s father-in-law) received the top prize, Max Weber the second.

Several years later, as a result of his growing reputation, Lechay was offered a teaching position in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. He turned it down, and the painter Stuart Edie was hired instead. But in 1945, he was again offered a position, and this time he accepted.

Lechay was hired to replace Philip Guston, who had just taken a position at Washington University. The sculptor Humbert Albrizio was already on the faculty; and Mauricio Lasansky, who was hired the same year to teach printmaking, arrived an hour ahead of Lechay. To abandon the city (he gave up his apartment to the then unknown novelist Bernard Malamud) and move to the Midwest, Lechay has said, "was a great new experience. We found the quiet of Iowa very noisy, much more than New York. This quiet was very difficult for us, but we got used to it."

Originally, Lechay had intended to stay in the Midwest for only a year. Instead, he continued to teach at the University of Iowa for three decades. When he retired in 1975, he and his wife Rose (who had been a librarian for many years at the Iowa City Public Library) moved to Wellfleet MA, where they spent their later years.

In 1965, ten years before his retirement. Lechay was contacted by a five-member faculty committee at the University of Northern Iowa (then called the State College of Iowa) in Cedar Falls. Lechay was commissioned to create a portrait of J.W. (Bill) Maucker, the school's president. The intention was to honor Maucker, who had served admirably for 15 years. But before he agreed, Lechay warned the faculty committee that "there's going to be a lot of protest."

As he explained in a 1995 interview in The Iowa Review, "I don't like doing these commission portraits, because I feel that the portrait would finally have to look like me, in spite of the fact that I'd be painting Maucker. I wanted to explain (to the committee) very carefully that Maucker will be there, and there will be some resemblance, but basically it's going to be my painting, it's going to be my way. I didn’t want to add anything to the mausoleum they've got. all these presidents' portraits."

Lechay was right. In March 1966, when his portrait of Maucker was completed and displayed prominently in the UNI Library, it prompted a controversy that went on for months, with most of the debate taking place in the student newspaper, The College Eye. To a lot of people, both faculty and students, there was not enough resemblance between Lechay's portrait and its subject. "The first time I saw the President's picture," lamented sociology professor Louis Bultena, "I muttered, 'If that looks like President Maucker then there is no reason why it should not be said that I look like the Queen of Sheba.” (Possessed of a rare sense of humor, as well as a talent for sleight of hand magic, Professor Bultena later confessed that ”I have since been told that I do bear a distinct resemblance to the Queen of Sheba, so it's all very confusing.")

Further, even if the painting were a sufficient likeness, it was dramatically at odds with what most people expected of a formal portrait. It was shockingly sketchy, with the figure made up of expressionist strokes of blues, grays, and browns (colors that would later prove significant), and it lacked the fastidious varnished detail of a Victorian-era Beaux Arts portrait. Indeed, it was painted so capriciously, its critics claimed, that Maucker's left hand appeared either claw-like or mangled, the remains of a third shoulder were visible above his left, and splotches on his face might be mistaken for shaving cream.

"What with all its vacuities, its poor craftsmanship, its general sloppiness, (and) its abortive character,” concluded influential UNI English professor Josef Fox in his weekly newspaper column called Obiter Scripta,* the Lechay portrait of Maucker was "a wretched work of art."

More than anyone, it was Fox (an outspoken civil libertarian, whom many admired, including myself) who fueled the controversy when—to everyone's surprise—on March 18, The College Eye published a one-sentence letter he had penned, which read: "I have an idea: if every student were to contribute 15 cents and every faculty member $1, we could buy the damn thing and burn it." (As he later explained, not very convincingly, citizens have every right to burn their own property, especially things that they regard as unworthy of preservation.)

Lechay's painting remained on display throughout those controversial months. While it was never physically harmed, it withstood a volley of verbal assaults. One letter writer suggested that the art faculty should buy the painting and the proceeds be used to commission a more conventional portrait. Another proposed that art selection committees in the future should represent a wider range of artistic tastes. Others called for restraint, and urged artists and other experts in the field to instruct the public on how best to look at the painting.

I recall all this because I was a sophomore art student at UNI at the time. I wrote "a column of the arts" in the student newspaper on the page opposite Dr. Fox's column. By happenstance, I was also a student that semester in his aesthetics seminar class.

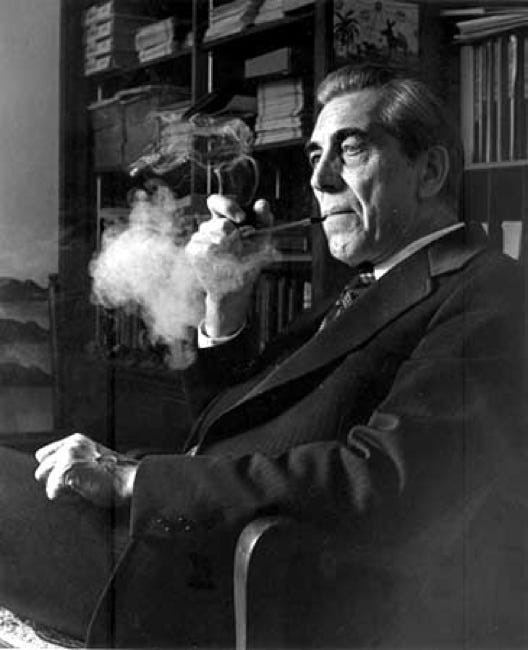

Joe Fox (as we fondly called him) was an unforgettable teacher, partly because of his theatrical pomposity, which he conveyed through various obvious props and mannerisms (black thick-rimmed glasses, a metal-stemmed pipe, and the resonant voice of reason) which, at least to students, made him both charismatic and comical. Invariably, he began each class by asking, "Are there any questions or comments?,” and in lectures, he frequently referred to Truth as "the real hot dope."

Many students parted company with Fox on his condemnation of the Lechay portrait of Maucker, and even more, on his suggestion that it be burned. But, as students, we were mere undergraduates, and we had little hope of challenging him by means of a logical, formal debate or in a newspaper editorial.

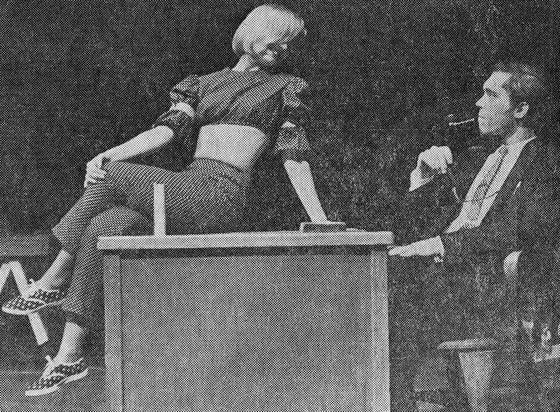

So we chose our own best weapons, not his. We wrote and produced a satirical play (titled The Portrait of a Bona Fired Agreement: How I Learned to Stop Screaming and Love the Damned Thing: A Play to be Burned) in which the main character was a pontifical pundit named Obita Scripter, described as "a solemn and distinguished ascetic (not to be confused with aesthetic) whose only possession is the Truth." Among the play’s other characters were The Popular Mind; Beauty; a blond seductress called The Real Hot Dope; Ralph the Red (based on Ralph Haskell. a red-bearded art professor who had the courage to stand up to Fox, at the risk of being sued); and a Greek Chorus of TKEs and Phi Sigs.

The play was published in the The College Eye on April 15, 1966, and by the following day, it had already been cast and rehearsed by the College Theatre Outcasts, with a performance scheduled for only three days later.

As literature, the play that I had written was dreadful and deadpan (it was just godawful), but the staged event was wonderful. It was directed by theatre student Terry Dyrland, who later became an Iowa legislator and who sometimes acted in productions at The Old Creamery Theatre in Amana IA. The lead role of Obita Scripter was played by Richard Devin (who went on to direct the Colorado Shakespeare Festival in Boulder), who used costume, pipe, glasses, make-up, voice, and mannerisms to make himself dauntingly similar to the real Dr. Fox.

Hundreds of students flocked to the performance, which was held in the Auditorium (now Lang Hall). It was rumored that even Josef Fox showed up, momentarily, to catch sight of, through the balcony door, the Fox-clad Devin on the stage.

Meanwhile, back in Fox's class, we students were required to submit a major research paper on some aspect of aesthetics. Defiantly, I chose to discuss the composition of the Lechay painting. When the paper was graded and returned, Fox had given it a D, because, as he explained to me, he had applied my own critical methods to the composition of the paper, and had found it sorely lacking. Yet inexplicably, I still somehow received a B as an overall course grade.

Ten days after the play's premiere, the campus returned to sobriety when, at the editor's request, President Maucker published a statement in the student newspaper relating his own reactions to the portrait. Maucker concluded that James Lechay “was not simply painting a portrait of me but was making a strong protest against the stress on the dignity of the office often found in presidential portraits."

Further, he believed that the portrait did convey a convincing likeness of him, that the artist had captured his essence somehow. "In the face itself and the cut of the shoulders,” he wrote, "it looks (to me) like I feel." He continued, ”I am sorry a good many of the staff and students are disappointed (by the portrait). But I think it will grow on all of us if given half a chance. I do wonder what impression it will convey to future generations of students and faculty who have had no contact with the genuine, puritanical original article—but my guess is that something more valid will get across than comes from the usual presidential portrait—and we can use photographs to show that I didn't have a mangled hand, a third shoulder, and feel sad or sinister about the shaving cream on my cheeks.” With that, Maucker concluded, "I like it and am enjoying the debate.”

As the semester concluded, so ended the Lechay controversy. But in large part, it was also defused by a talk on May 2 by the artist James Lechay who graciously agreed to come to the UNI campus and reply to provocative questions about the portrait.

Gray-haired, ruggedly handsome, and eloquent, at the end of an hour Lechay had won over the overflow crowd of hundreds of faculty and students. His answers were tape-recorded, then printed almost fully in The College Eye a few days later.

What he had made was "a portrait of me," he explained, "It's Maucker through Lechay." When asked about the responsibility of artists to the lay public, he responded: "I think it's terrible and arrogant of anybody to consider the public as something of low mentality. You know, write dumb, paint dumb for the public. I think you should go on the assumption that the public is intelligent and has the ability to learn and to catch on to things. So my responsibility as an artist is to do my best without compromising, knowing that the public will catch on. It always has.”

Today, Lechay's once shocking painting hangs quietly, largely unnoticed, in the university’s Maucker Student Union. I see it on rare occasion, and to me it looks even finer than it did in 1966.

In 1998, I had lunch with the aging Bill Maucker, who had retired many years before, but was still living in Cedar Falls. He was easy to recognize, because (as he had often been told) as he grew older, he looked more like the Lechay portrait than he had 32 years before. Comparing the two, the portrait and its sitter, I was reminded of Pablo Picasso's reply when people complained that Gertrude Stein did not look like his famous portrait of her. "Don't worry," he said, "she eventually will."

Sadly, by that time, Josef Fox had died. Only months after his retirement, he had collapsed while mowing his lawn in Peacham VT. Much earlier though, in the early 1970s, when he was still teaching, I had lunch on campus with him and John Volker (a friend and former classmate who was a designer and photographer). I had returned to Iowa after graduate school and a stint in the US Marine Corps, and I asked Joe Fox if he had ever served in the military.

"Oh, yes," he replied, "I certainly did, I signed up during World War II, but I didn't get the assignment I volunteered for. I wanted to be an Air Force pilot but when I took the tests they discovered I was blue-gray colorblind. In fact I'm so colorblind," he continued, "my wife has to pick out my necktie in the morning."

Blue-gray colorblind? John and I rolled our eyes as we glanced at one another across the table: Did he say blue-gray colorblind? The lunch continued, and we didn't say a word to Joe about the old painting controversy. But as we left the Union, we paused to reflect for a moment in front of James Lechay's infamous portrait of President Maucker—in which virtually all the colors consist of blues, grays, and subtle hue-mixed grays and browns.

Photographer unknown

Photographer unknown

The portrait was painted so capriciously, its critics claimed, that President Maucker's left hand appeared either claw-like or mangled, the remains of a third shoulder were visible above his left, and splotches on his face might be mistaken for shaving cream.

Above James Lechay, Blue is for Bass (1949). Oil on canvas. 33.5”h x 43”w. Permanent Art Collection, University of Northern Iowa.

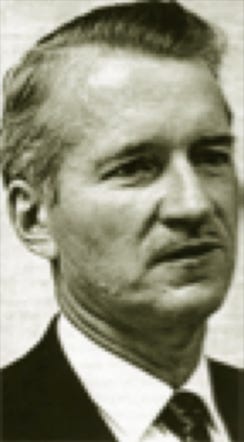

Left Portrait photograph of UNI President J.W. (Bill) Maucker (c1966).

“In the face itself and the cut of the shoulders,” Maucker explained, “it looks (to me) like I feel.”

• • •

Above Portrait photograph of a younger James Lechay (n.d.). Archives of American Art.

Above Portrait photograph of a younger James Lechay (n.d.) in his studio in New York. Archives of American Art.

• • •

Left UNI Philosophy Professor Josef W. Fox as he appeared much earlier in his teaching career.

Above A contemplative Josef Fox in the last years of his teaching career.

• • •

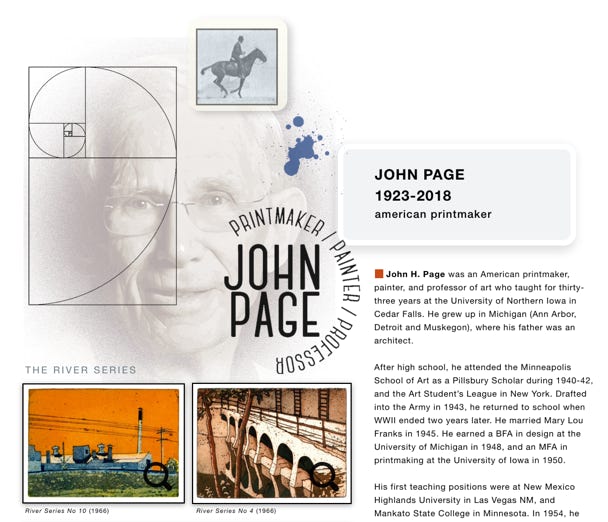

Above A scene in the play in which the character based on Dr. Fox (Obita Scripter), as played by theatre student Richard Devin, is conversing with The Real Hot Dope, as played by Judith (Lauer) Adamson, who went on to become the Costume Director at the University of North Carolina. He is asking, “Are there any questions or comments?”

Above The script of the infamous play as published in The College Eye on April 15, 1966.

Above The playwright (left) confronted by the character Obiter Scripta (aka Richard Devin).

*Obiter Scripta (Latin for “passing thoughts”) had been used by Harvard philosopher George Santayana in 1936 as the title of his book of collected essays. In Humanities class in 1964, Josef Fox said that his favorite philosopher was Baruch Spinoza.

• • •

James Lechay

It is a portrait of me—it’s Maucker through Lechay.

Maucker concluded that Lechay “was not simply painting a portrait of me but was making a strong protest against the stress on the dignity of the office often found in presidential portraits."

• • •

Eugene Speicher

A portrait is a painting in which something is wrong with the mouth.

Charles Dickens

There are only two styles of portrait painting: the serious and the smirk.

SOURCES

When this essay was written in 1998, I sent pre-publication drafts to a handful of people who had been on campus in 1966. Two of those people were J.W. (Bill) Maucker, who was living in Cedar Falls, and James Lechay, who, at age 95, was living in Wellfleet MA, still painting and exhibiting in New York. Lechay enjoyed the article, and replied with two kind hand-written notes. Bill Maucker also sent a kind response, and that led to a wonderful lunch.

In addition, I have other letters from John Page (who had been head of the portrait selection committee) and Ella Mae Gogel (widow of art faculty member Ken Gogel), all of which will be donated to the UNI Archives and Special Collections in the near future.

Various articles and letters in 1966 issues of The College Eye can easily be found online. See also T.H. Thompson, ed., Josef Fox: A Faith in Reason: Essays and Addresses (Cedar Falls: North American Review, 1982); and S. London, “An Interview with James Lechay” in Iowa Review Vol 25 No 1 (1995), pp. 137-148.—RB

Philip Evergood at UNI

CLICK ON LABELS TO ACCESS LINKS