Photographer unknown

DREAMS OF FIELDS

When Salvador Dali

Crossed Paths

with Sigmund Freud—

and Iowa

This essay was published initially in Tractor: Iowa Arts and Culture (Cedar Rapids IA), 2000. Later, it was featured in an issue of Ballast Quarterly Review, Spring 2003, and as a printed booklet. Copyright © by Roy R. Behrens.

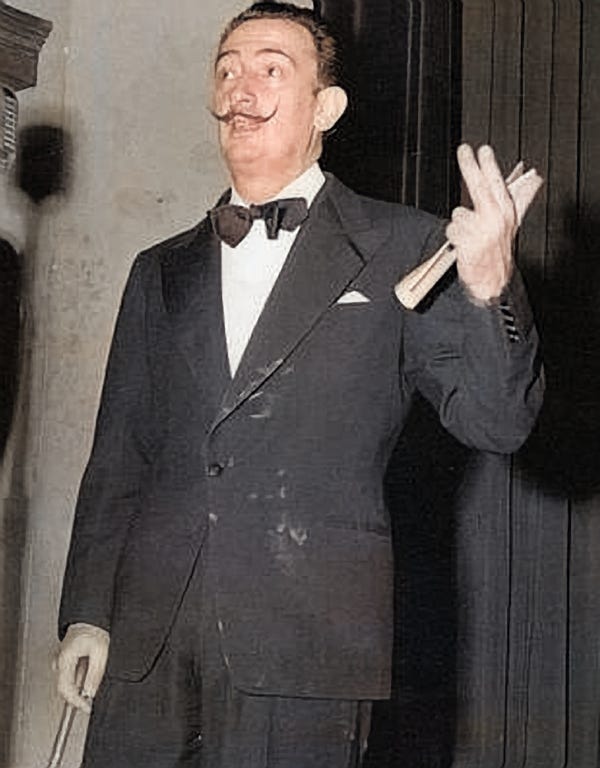

Above News photograph of Salvador Dali as he appeared in February 1952 at a news conference at the Russell Lamson Hotel in Waterloo, Iowa. Note the ominous rhinoceros-hide cane on the table before him.

Photographer unknown

• • •

Photographer unknown

Sigmund Freud

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

Below Salvador Dali (center) at a press conference in February 1952, at the Russell Lamson Hotel in Waterloo, Iowa, on the morning of the day of his university lecture. He is equipped with his rhinoceros-hide cane. Donald A. Kelly, the UNI journalist whose question prompted Dali to slam his cane on the table, is sitting at the far right of the photograph. Kelly and Dali appear to be looking at the university president J.W. (Bill) Maucker, who is in the center foreground with his back to the camera. The man between Maucker and Kelly taking notes may be Des Moines Register art critic George Shane.

WHEN THE SPANISH Surrealist Salvador Dali (1904-1989) was asked to name his favorite animal, he replied, “Filet of sole.” He also said, “I am surrealism,” which he then defined as “the systemization of confusion.” Dali was as talented at self-promotion and money-making as he was at painting. As was pointed out by the French poet André Breton, an anagram for Dali’s name is Avida Dollars, a hybrid Spanish-English term for “eager for dollars.”

Surrealism, which was founded by Breton in 1922, was a style of art and literature that grew out of an unlikely marriage of art with psychoanalysis. Its artistic parent was a Zurich-based “anti-art” movement called Dada. Dada began as a protest of World War I and deliberately tried to provoke its audiences through chance, nonsense, errors, and contradiction—in other words, by the systemization of confusion.

During the same war, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic method of “free association” (to say aloud, while lying on a couch, whatever comes to mind) had been used with some success to treat the victims of trench warfare. Working with shell-shocked soldiers in a hospital, it was Breton who saw the connection between Freud’s famous “talking cure” and the Dadaists’ nonsense-producing techniques like automatic writing, radical juxtaposition, and the exquisite corpse. But the link between Freud and Breton was direct, and they actually met in Vienna in 1921.

In 1938, Dali also met Freud, in London, in a meeting that, according to Dali, was an utter failure. Freud was old and ill by then. Only a month earlier he had withstood a Nazi raid of his home in Vienna, had fled to England, and would soon die of cancer of the jaw. Under the circumstances, he could not have been greatly amused by a crank with billiard-ball eyes and a moustache as sharp as a scorpion’s tail. “Contrary to my hopes,” Dali recalled of their meeting, “we spoke little, but we devoured each other with our eyes.”

Dali, then in his mid-30s, was already widely known for his “critical paranoid” paintings of dreams in which limp watches are suspended from trees, giraffes have been set afire, and Mae West is a cushioned room interior. During his visit, Dali tried to convince Freud to look at an article that he had just published on paranoia. Opening the magazine, he begged Freud to read it not as a “surrealist diversion” but as an “ambitiously scientific article.” Still, Dali reported later, “Freud continued to stare at me without paying the slightest attention to my magazine.”

Faced with what he later termed “imperturbable indifference,” Dali made his voice grow “sharper and more insistent.” As the meeting ended, Dali said, Freud continued to look at him “with a fixity in which his whole being seemed to converge,” then turned and said, in Dali’s presence, to Stefan Zweig, the Austrian writer who had arranged the meeting, “I have never seen a more complete example of a Spaniard. What a fanatic!”

How wonderfully appropriate (how dreamlike!) that the painter of dreams should be incompatible with the father of dream analysis. No less appropriate, however, is the discovery that Dali’s interpretation of Freud’s reaction was mistaken, and that Freud actually found their encounter that afternoon both pleasant and instructive. (In other words, Dali really was paranoid.) “I really owe you thanks for bringing yesterday’s visitor,” Freud wrote to Zweig on the day after the meeting. “For until now I have been inclined to regard the surrealists, who apparently have adopted me as their patron saint, as complete fools (let us say 95 percent, as with alcohol). That young Spaniard [Dali], with his candid fantastical eyes and his undeniable technical mastery, has changed my estimate."

IF ANY ENCOUNTER is more bizarre, any juxtaposition more radical, it may be the circumstances of 14 years later when Dali was briefly a visitor at the University of Northern Iowa (then called Iowa State Teachers College) in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Two years after his meeting with Freud, Dali had moved to the US, where he lived and worked for 15 years, mostly in New York. Near the end of that period, having abandoned his critical paranoid stance and having been renounced by his fellow surrealists for his political beliefs, he agreed to a series of lectures in which he toured the country with his wife Gala, giving slide and chalkboard talks about his new approach to art called “nuclear mysticism.”

In 1952 Dali gave ten presentations at schools and museums throughout the US, beginning with a lecture on “Revolution and Tradition in Modern Painting” at UNI on the evening of Wednesday, Feb. 6. His visit had been arranged by Herbert V. Hake, chairman of the college’s Lecture-Concert Series Committee, who had chosen Dali as a replacement for Edward R. Murrow, the celebrated CBS news analyst, who was unable to appear.

Dali was paid a then-substantial speaking fee of $1,000 (the only more expensive act was the Salzburg Marionettes). He, Gala and Mr. and Mrs. A. Reynolds Morse (a wealthy couple from Cleveland, Ohio, who owned 16 Dali paintings, and who later established the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Fla.) arrived from Chicago by passenger train on the evening of Feb. 5. They were housed in downtown Waterloo at the Russell Lamson Hotel where it had been agreed that at 10 o’clock the next morning Dali would hold a press conference.

On Wednesday evening, more than 1,300 people gathered for Dali’s lecture, which began at 8 pm in the auditorium of what is now Lang Hall. It was a huge audience for a small school, but dozens more might have attended, wrote Des Moines Register art critic George Shane, had it not taken place at the same time as an exhibition match by five Japanese Olympic wrestlers in the men’s gymnasium across campus.

During his slide-illustrated lecture, Dali foretold the emergence of a new traditionalism, which he was the leading practitioner of, wherein artists would abandon the then popular abstract expressionism—“If you believe nothing, you can paint nothing”—and return to traditional narrative art, to “spiritual classicism.” It would be a second Renaissance, Dali predicted, in which academic painting practices (at which he excelled) would close the gap between science and religion, between rationality and mysticism.

“In spite of a tremendous language barrier,” reported the student newspaper, Dali’s audience of faculty, students and townspeople was both “charmed and fascinated” by his presentation. “A Spaniard by birth,” the article continued, Dali “speaks English with a labored accent, seasoned with frequent French connectives and pronunciations. His colorful gestures, highly waxed moustache, distinctive cane, and ready wit added to his personal appeal.”

In the audience that evening was Lester Longman, head of the School of Art and Art History at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. When the talk ended, he asked Dali about the political leanings of another Spaniard, Pablo Picasso. (Were Picasso’s paintings influenced by Communist doctrine? No, no, replied Dali, they cannot even be exhibited in Russia.) Others wondered why an artist as famous as Dali had agreed to visit Iowa in the middle of winter. (The answer, as it turned out, was that he had no grasp of the vastness of America; looking at the map, Dali thought that Cedar Falls, Kansas City, Houston, and his other scheduled stops were only a brief train ride from Chicago.)

Also in the audience was the painter Paul R. Smith, a UI graduate who had recently joined the UNI art faculty. Before the lecture, Smith had deliberately, cleverly covered the speaker’s table and lectern with brown kraft paper, in the hope that the artist might doodle or sketch inadvertently during the program. Unfortunately, as Smith recalls, sometime after the lecture that evening, when he went back to the auditorium “to get the notes, scratches and drawings, they had been disposed of by the maintenance people and lost.”

Later that evening Smith and other UNI art faculty members, along with Longman and Shane, attended a party for Dali, which had been arranged by Harry G. Guillaume, the head of the art department. Hosted by Corley Conlon, a legendary senior member of the art faculty, the party was held at her unconventional self-designed cherry-red home (a dwelling in which there were no doors in the basement so that she could host uproarious faculty parties in which everyone wore roller skates) on Seerley Boulevard just west of the corner of Seerley and Main.

Throughout the party, Smith remembers, “Dali and Longman spent most of the time talking in French. Dali, of course, would start an English sentence and then end two-thirds of it in French.” Dali said that he liked the Midwest because it reminded him of his Spanish homeland. The corn in Iowa, he explained, “is the same as we have, except that ours is the red variety. We call it Arabian wheat, and the houses in Catalonia are beautiful when the ears are hung over the second-floor balconies to dry.”

IT WAS NOT Dali’s thick accent but his distinctive rhinoceros-hide cane, “which he used as sort of a riding crop and pointer,” that left the most lasting impression that day on Donald A. Kelly—and for good reason.

Kelly, who moved to Ohio after retirement, was a staff member at the time in the UNI Public Relations Office. He was not at the party that followed Dali’s talk, but he was among a small group of local journalists who attended the press conference in Waterloo earlier that morning.

During the question-and-answer period, Kelly asked Dali “if art critics might think his shift from surrealism to nuclear mysticism could be a publicity ploy rather than genuine.” The artist’s alarming and sudden response was unforgettable: “He glared at me,” recalled Kelly, “and slammed his cane on the table. If he responded verbally, I don’t remember what he said.”

Soon after, the session ended as the ex-surrealist painter gave a splendid example of the systemization of confusion—wide-eyed, chin up, and adjusting the barbs of his moustache, he said: “Myself disagrees avec everybody today.” What a fanatic!

• • •

Salvador Dali

Every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dali, and I ask myself, wonderstruck, what prodigious thing will he do today, this Salvador Dali.

James Thurber—

Let me be the first to admit that the naked truth about me is to the naked truth about Salvador Dali as an old ukulele in the attic is to a piano in a tree, and I mean a piano with breasts.

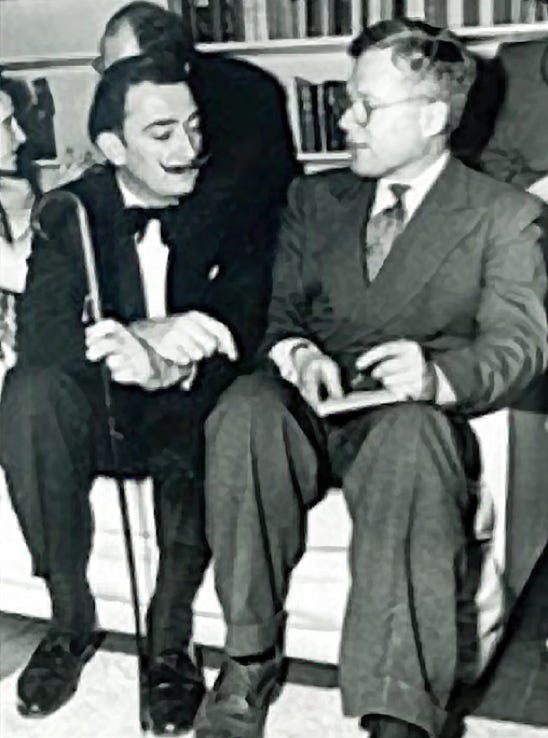

Above The man seated on the right is the art critic for the Des Moines Register, George Shane. To the left of course is Dali, cane in hand. This photograph was no doubt taken during the evening art faculty party at Corley Conlon’s ranch style home on Seerley Boulevard in Cedar Falls. Still intact, it is the house just east of the Hearst Center for the Arts, of which it is also now an annex.

Left (top) Hermann Rohrschach inkblot used in psychological assessments (1921), and (bottom) Bhutanitis lidderdalii, a stunningly exotic swallowtail butterfly known as the Bhutan glory, found in Bhutan, India and Southeast Asia.

Above There is an excellent video on this subject, produced by Roy R. Behrens (2022), of Dali’s visit to Iowa in 1952. About twenty minutes in length, it is free to view online. For classroom purposes, it begins with a brief but poignant overview of Dada, Surrealism and Freud in relation to World War I. Click here to access the online video.

Anon

—How many Surrealists does it take to screw in a light bulb?

—Two. One to hold the giraffe and the other to fill the bathtub with brightly colored machine tools.

Salvador Dali—

I do not take drugs. I am drugs.

Woody Allen—

This guy goes to a psychiatrist and says, “Doc, my brother’s crazy. He thinks he’s a chicken.” And the doctor says, “Why don’t you turn him in?” And the guy says, “I would, but I need the eggs.”

Samuel Goldwyn—

Anyone who would go to a psychiatrist ought to have his head examined.

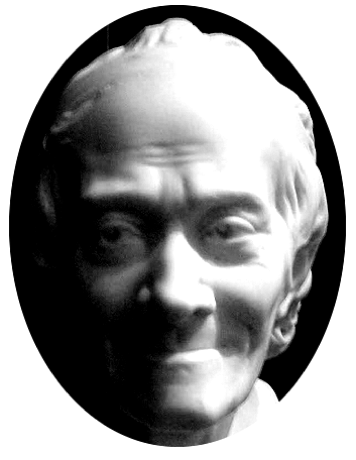

Above In a detail of one of Dali’s painting, Slave Market with Disappearing Bust of Voltaire (1940), on which the above drawing is based, one can interpret a cluster of shapes in the center of the painting as the figures of two nuns, or, by a switch of attention, as the image of Houdon’s famous portrait bust of the French philosopher Voltaire. aIn a detail of one of Dali’s

Left Philippe Halsman’s famous photograph of Salvador Dali and three airborne cats, titled Dali Atomicus (1948). This is an early example of Halsman’s many photographs of famous people jumping. It was Halsman’s idea, and came about as an alternative to an initial suggestion by Dali that they photograph a duck being blow up by dynamite (Why-ah duck? Why-ah no chicken?). Thank goodness, they settled on this approach instead. Public domain.

Below A selection of Halsman’s “jumpography” portraits were published in The Jump Book. First produced in 1959 by Simon and Schuster (even their trademark “sowing man” was redrawn as jumping), the book has since been reissued.

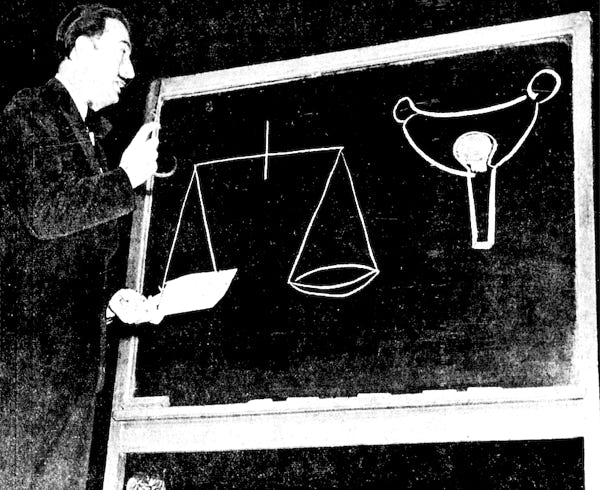

Above Photographs of Dali lecturing in Lang Hall at UNI in February 1952. In the top photo, notice the chalk dust on his tuxedo.

Brad Holland

Surrealism: An archaic term. Formerly an art movement. No longer distinguishable from everyday life.

• • •

André Breton

[anticipating Donald Trump?]

The simplest surrealist act consists of going down into the streets revolver in hand, and shooting at random.

Ce n’est pas un cigare

SOURCES

Details of Dali’s encounter with Freud can be found in S. Room and J.W. Slap’s “Freud and Dali: Personal Moments” in American Imago Vol 10 No 4 (Winter 1983), pp. 344-345; and in Gilbert Rose’s Trauma and Mastery in Life and Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), pp. 7-14. There are two photographs of Dali at his UNI lecture and news conference in A. Reynolds Morse’s Salvador Dali - Pablo Picasso: A Preliminary Study of Their Similarities and Differences (Cleveland OH: The Salvador Dali Museum, 1973). Others are from other sources. For help in researching this essay, the author is grateful to Gerald Peterson (UNI Special Collections Emeritus Archivist), Paul R. Smith, Donald A. Kelly, frje echeveria, Todd Kimm at Tractor magazine, and the UNI Graduate College. Some of the photographs in this article have been digitally colorized, using AI software.—RB

Clifton Fadiman

Gertrude Stein was the mama of Dada.