Booklet Cover / Roy R. Behrens

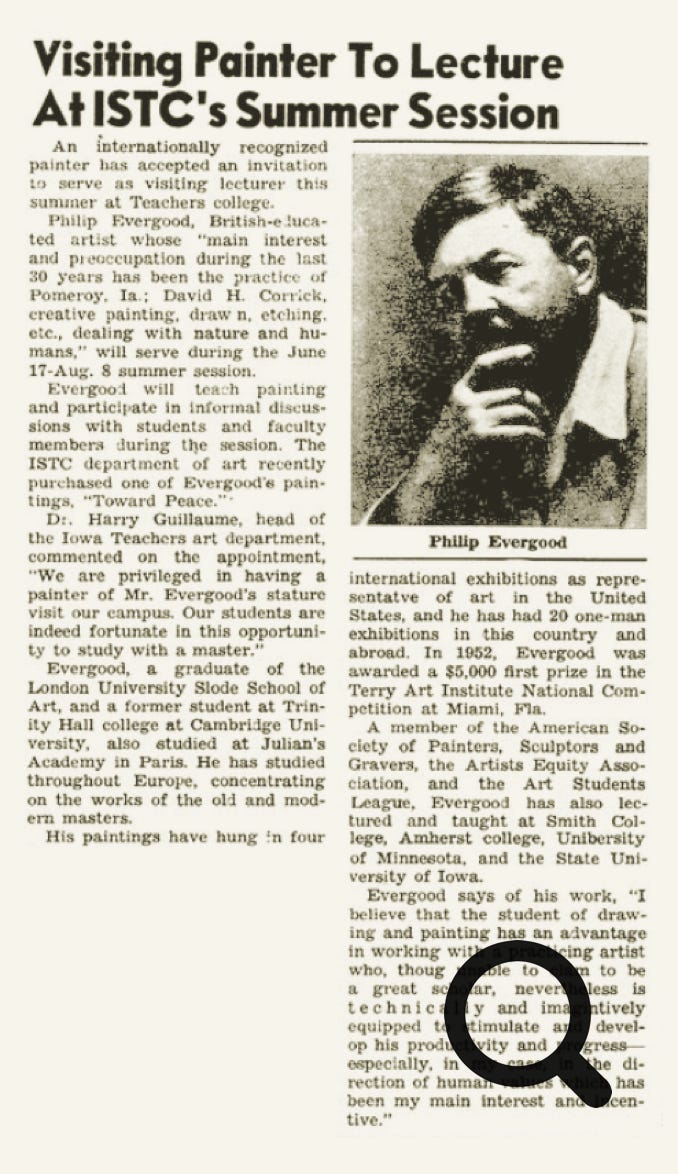

DURING THE summers of 1957 and 1958, the American painter Philip Evergood (1901-1973) was a visiting artist at the University of Northern Iowa (in Cedar Falls), known then as Iowa State Teachers College.

Evergood was already a well-known artist, because of the critical interest in his exotic figure paintings, in which he combined certain aspects of surrealism with a deliberate primitivism, but also because of his dalliance with American Socialism, which was widely considered subversive in the Red scare of the McCarthy Era.

Through two organizations in New York, Artists Equity and the American Contemporary Artists Gallery, Evergood became acquainted with Paul R. Smith, a professor of painting at UNI, and it was apparently Smith who convinced Evergood to teach in Cedar Falls for the summer.

During that first summer, Evergood taught painting in Room 201 of the Arts and Industries Building (now called Latham Hall). He was popular with the students, partly because of his boisterous laugh and lively sense of humor. But he was far less popular with some of the faculty. "Phil had a booming voice," Smith remembers, "and when he talked to the class his voice carried down the hall, and he bothered some of the other instructors."

Smith also recalls a classroom incident in which Evergood wrote on the chalkboard the ingredients for an egg-oil painting medium. "Afterwards," says Smith, "some students added to the list ‘a cup of beer.’ Upon returning to the classroom, another instructor had faithfully copied the list and included the cup of beer which he dutifully mixed and used in his paintings. Phil thought that was terrific."*

When Evergood returned for a second summer, the experience was not as pleasant as the first. During his previous visit, he had completed a large painting, titled The Peaceful Arts, which remained on a wall in the hallway as he worked on it. At the end of the first summer, apparently pleased with his Iowa stay, Evergood offered the painting to the school. However, when he returned the following year, he was confronted by two members of the UNI art faculty who voiced their strong dislike for the painting, and in a moment of anger, he took the artwork off the wall and shipped it back to New York.

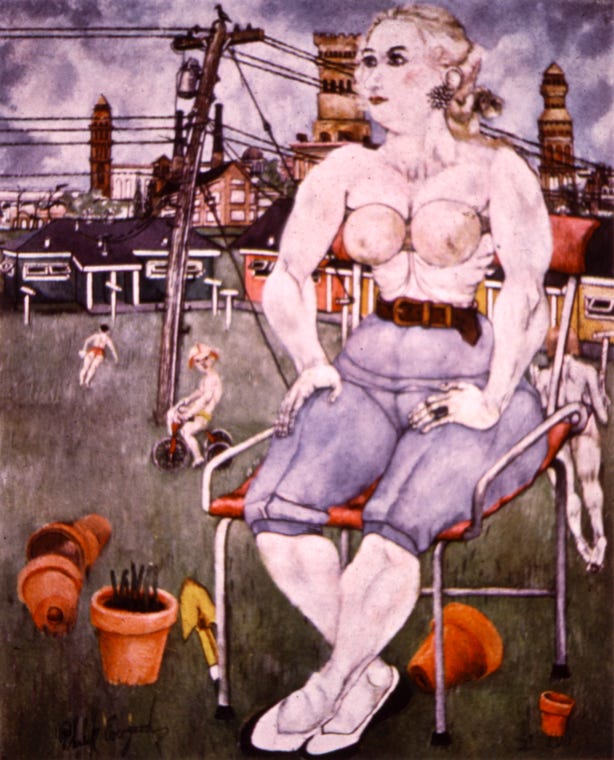

Other things also happened that summer: Evergood (whose wife had remained on the East Coast) fell in love with an older woman student who lived in what had been army quonset huts that served as student housing on the south edge of campus. Before leaving, he created a portrait of her in Woman of Iowa, which shows her sitting outdoors in a lawn chair, dressed in pedal pushers and a halter top, with the UNI campus and ranch-style student houses, made of painted concrete blocks, in the background.

In addition, Evergood collaborated with UNI printmaking professor John Page (who was teaching next door in Room 202) on an etching of a younger woman, dressed only in her lingerie, standing by a bed and talking on the phone. Titled Mom I’m Engaged, it was a parody of a then popular magazine ad for the Bell Telephone Company. It came about when Evergood mentioned to Page that he had drawn on etching plates about twenty years earlier and enjoyed the process.

“Without asking his approval," Page remembers, "I got a 14 x 17 inch copper plate, grounded it, and gave it to him, saying I would help etch and print it if he wanted me to." Nothing happened for quite a while, and then, near the end of the summer, Evergood telephoned Page and said that his drawing was ready to etch.

That evening, Evergood came to dinner at John and Mary Lou Page’s home, which was also John’s printmaking studio. "I put the copper plate into the acid bath while we ate dinner," recalls Page, "then Phil and I went downstairs to proof it. After some line changes, he wanted some aquatint tones, so we did all those, proofing quite a few times, etching and scraping the plate in between. This went on until the early hours of the morning. Mary Lou, who had gone to bed and was asleep two floors above, was awakened by the loud whoop of laughter of Phil when the final print came out." Later, Page printed the plate in an edition of fifteen, one of which he later gave to the university.

During Evergood’s UNI visits, two other works of his were added to the Permanent Collection of Art. Purchased from the artist at extremely low prices (one, for example, was $50) were an oil painting titled Towards Peace and an exquisite pen and ink wash drawing of cats. These remained in the university’s collection until the late 1970s, when both works disappeared. Neither artwork has been recovered.

Evergood’s family name (which had been changed from the Polish Jewish name of Blashki to a variant of Immergut, his father’s mother’s family name) was somewhat ironic, since, throughout his life, he experienced a number of bizarre misfortunes, some of which were life-threatening. In 1941, for example, six weeks after an operation for cancer, he was near death when it was found that a surgical sponge had been left in his abdomen.

In 1958, when he drove back to New York from Cedar Falls in his old convertible, he took with him a carload of paintings completed while at UNI; and a large ceiling fan from Berg’s Drugstore on College Hill, which he obtained in exchange for two paintings. Arriving in New York, he parked outside the ACA Gallery; but when he came out, he found that the top of the car had been slashed, and the fan and a few of the paintings were gone.

Nine years later, while carrying his aged mastiff dog, he slipped on the stairs of his Connecticut home, hit his head on a sidewall, and ran a nail so far into his skull that it had to be removed surgically.

In the meantime, Paul R. Smith had left UNI in 1965 to become head of the art department at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota. Once there, he nominated Evergood for an honorary doctorate, which was slated to be given to him at the school’s commencement in June 1968. However, in late 1967, having barely recovered from skull surgery, Evergood accidentally set fire to his shirt while lighting his pipe, which resulted in terrible burns to his chest, neck, and back. Hospitalized for fifteen weeks, it was soon discovered that he also had Parkinson’s disease.

In his few remaining years, Evergood’s health declined rapidly, and he complained increasingly of chest pains. On the evening of March 11, 1973, he may have had a heart attack, but the official cause of death was smoke inhalation—while drinking and smoking alone in his room at his home in Bridgewater CT, he dozed off in a sitting position and set fire to the mattress.**

• • •

Notes

*According to John Page (who copied down the ingredients before the students added beer), Evergood’s formula for an "Egg-Oil-Varnish Emulsion for Glazing and as a Medium" was as follows: "1 egg. 1/2 egg shell linseed oil; 1/2 eggshell damar varnish. Beat egg. Add oil drop by drop. Add varnish the same way. When like mayonnaise add 4 drops of carbolic acid, or 6 drops of oil of cloves, or 6 drops of formaldehyde. Mix with dry colors or with oil. Use gasoline to clean brushes (no lead, etc.)."

**For further information on the life of Philip Evergood, see Oliver Larkin, 20 Years of Evergood (New York: ACA Gallery / Simon and Schuster, 1946); John I. H. Baur, Philip Evergood (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1975); and, especially, Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (Cranbury NJ: Center Gallery / Associated University Presses, 1987).

Acknowledgments

Of help in preparing this article were Matthew DeLay, who was Interim Director of the UNI Gallery of Art at the time it was written, and who provided access to Permanent Collection documents, and to conversations and/or correspondence with UNI Emeritus Professors David Delafield, John Page, and Paul R. Smith (all of whom have since passed on).

THE GOOD,

THE BAD—

AND PHILIP EVERGOOD

A New York Artist’s

Adventures in the Midwest

This essay was published initially in Tractor: Iowa Arts and Culture (Spring 1998), then reprinted as a booklet. Copyright © by Roy R. Behrens.

Sources

The quotes in the margins on this page are from an interview with Philip Evergood, on December 3, 1968. It took place at the artist’s home in Bridgewater CT, and was conducted by Forrest Selvig for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The transcript of the entire interview, along with that of an earlier session from 1959, can be accessed at the website of the Archives of American Art.

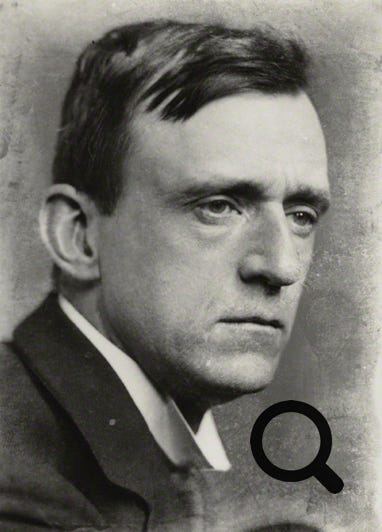

[Portrait of Philip Evergood], ca. 1942 / Deana Hoffman, photographer. Photographic print : 1 item : b&w ; 11 x 08 cm. Philip Evergood papers, 1910-1970. Archives of American Art. Public domain.

Philip Evergood—

[Recalling the experience of studying at the Academie Julian in Paris in the mid-1920s] “I was studying [drawing] with Jean-Paul Laurens. And Laurens was a prima donna who would waltz into the class once a week or two, stroll around with a big black cape on and look at a painting or a drawing, and shrug his shoulders, and say, Je ne sais pas; je ne sais pas. Qu'est que ce? Qu'est que ce? ‘What does I mean?’ ‘I don't know.’ He wouldn't be telling you, ‘Look, man, it's got good qualities here and there but you'll improve it if you do something.’ There was nothing really constructive in his criticism. So I got bored. The most interesting thing about the Academie Julian when I was there were the dirty jokes of the students and the models and the girls and the beer tavern opposite where we would go a couple of times during the day and have a few beers. That's what interested me most.”

•••

Philip Evergood—

[Recalling how he was admitted to the Slade School of Art in London, where he studied with the legendary Henry Tonks] “And he [Evergood’s teacher Harvard Thomas] took me by the hand and took me out to Tonks at the Slade. And going in through the great doorway of this big institution was an awesome experience. I had my little portfolio with my little imaginative Biblical drawings and things that I had done. And Thomas gave me the confidence to face the great Tonks. He rapped on Tonks’ study door and ushered me in. And Tonks said, ‘Sit down. Open your portfolio. Don't be afraid. Show me what you've got.’ And I did. And Tonks looked at my drawings very seriously. I had been told to bring not only imaginative figure drawings but also some careful drawings of hands and faces and eyes and ears to show whether I had any ability to draw from life. And Tonks was very kind. He thought for a while. And then he said, ‘Well, my dear man, I see an awful lot of young people's work and you can’t draw and you might as well know it. But you have one quality which I like. You can make me laugh. So I will take you in the Slade.’ And I said, ‘What do I do?’ He said, ‘What do you do? You go out to the desk and you get a drawing board and you get a piece of paper and you start to work.’ And that was the beginning.”

Philip Evergood Woman of Iowa. Oil on canvas, 35 x 30 in (1958), current location uncertain. The background is a whimsical interpretation of the campus of the University of Northern Iowa. While some of the buildings are recognizable, the real campus has only one campanile.

Philip Evergood—

“[American painter George] Luks was mostly concerned with Luks. And with his great big beautiful heart he loved everyone. Loved everything. Loved people. He had a great sense of humor. Did you ever hear the story of Luks walking through the Columbus Circle when they were painting these great big cigarette ads as big as a skyscraper, you know, with scaffolding and these scaffolds that can be lifted up and down with ropes, pulleys?…Well, he looked up and here was a little tiny speck of a man on the side of his great big building painting the face of a smiling woman—big tremendous face, as big as this room the face was—smoking a cigarette or something with something like ‘Buy Lucky Strike Cigarettes’ underneath. And Luks called up. He was struggling, this little fly up there, with an eye probably ten feet long. And he couldn't get the eye. And Luks, little speck down below, called up, ‘Hey, man, hey! I'm an artist, a great artist. Do you want me to give you some help on that eye?’ And the guy said, ‘Sure! Why sure!’ And he let down the little scaffolding thing. And Luks got onto it. He took these brushes which were about a foot long and got up there and painted the eye.”

•••

News article, College Eye. May 29, 1957, page 3

Philip Evergood—

“[While living in a loft on 14th Street in New York, I] began to rub shoulders with all kinds of people—girls working in the five-and-ten-cent store opposite, and a man with no legs or arms going by on his little trolley singing all day long with his little cup, singing, ‘All of me, why not take all of me.’ Finally, I was awful. I was really vilely awful. But it drove me mad so much from that early morning till late in the evening—’All of me’—that I couldn’t resist the temptation to open my window and call out, ‘I say, old fellow, I’m a struggling artist up here trying to concentrate. Will you be kind enough to change that tune to something else? Anything. But I can’t stand “All of me” anymore.’…This is tragic. He changed it and he got no nickels in the cup. So he went back to it a few days later. But I felt like an awful heel at the time for losing my temper and asking him to change the tune.”