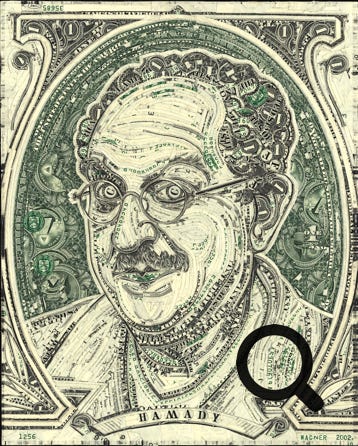

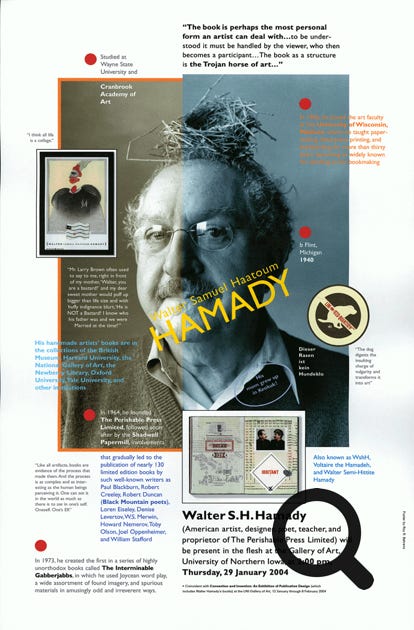

YEARS AGO, a friend of Walter Hamady said (as Walter himself tells the story), “right in front of my mother, ‘Walter, you are a bastard!’ And my dear sweet mother pulled up bigger than life-size and with huffy indignation said, ‘He is not a bastard! I know who his father was and we were married at the time!’”

Hamady was still young when his parents’ marriage fell apart. His father was descended from Lebanese immigrants who had founded a prominent grocery store chain in Flint, Michigan. His mother was a physician (a pediatrician and, later, a psychiatrist). Also, he is quick to add, she was a “book nut” from Keokuk, Iowa. One product of that marriage was Walter Samuel Haatoum Hamady, who also answers to the names of Walter Semi-Hittite Hamady, WshH, or Voltaire the Hamadeh.

However he disguises himself, Hamady is a designer, typographer, printer, papermaker, book artist, collagist, assemblagist—and book nut. From 1966 until his retirement, he was an influential teacher at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in a studio known as 645, simply because that was the room number. During those many years, among his scores of students were Charles Alexander, Janet Ballweg, Gretchen Lee Coles, Lester Harrison Doré, Jim A. Escalante, Marta Gomez, Susan Gosin, Beth Grabowski, Lane Hall, Kevin Henkes, Kent Kasuboske, Katherine Currie Kuehn, Jim Lee, Ruth Lingen, Shiere M. Melin, Steve Miller, Lisa Moline, Jeffrey W. Morin, Stephanie Newman-James, Bonnie O'Connell, Mary Jo Pauly, Cathie Ruggie Saunders, Susi Schneider, Pati Scobey, Bonnie Stahlecker, Margaret Sunday, Barbara Tetenbaum, Walter R. Tisdale, and Debra A. Weier. There were innumerable others as well.

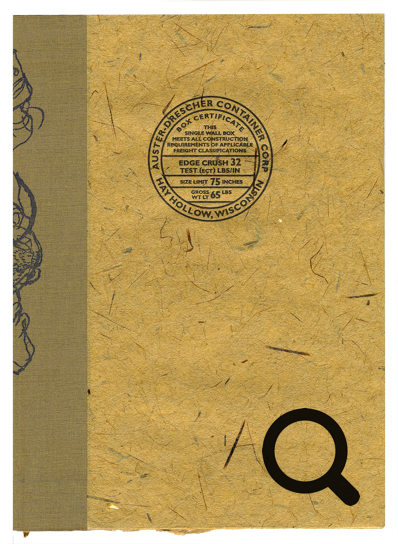

Long after his retirement, Hamady continues to be lauded for his achievements as a teacher. At the same time, he is as well or better known as the originator and proprietor of one of the country’s most admired and innovative private presses. At its founding, he chose the name The Perishable Press Limited because, as he explains, “It reflects the human condition, which is both perishable and limited.” But also he adds with an impish wink that he was looking for “another word beginning with the letter P to go with the word ‘press’”.

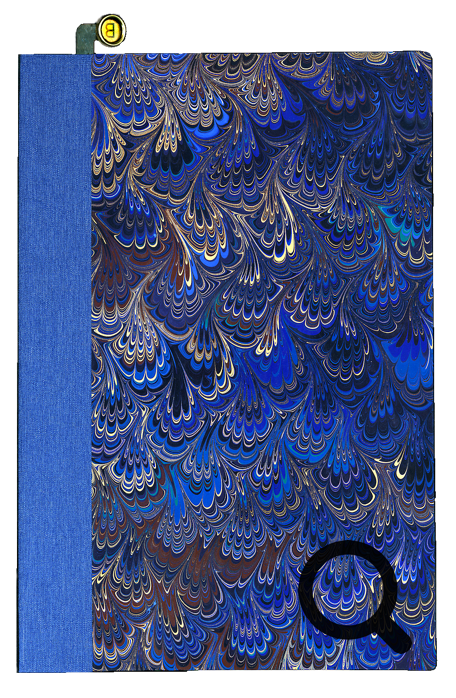

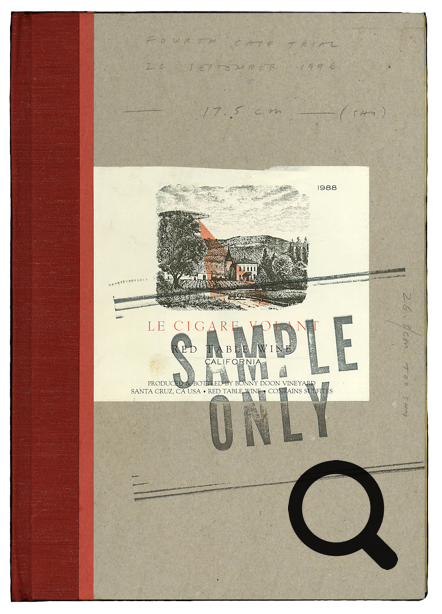

From the very onset, unlike most staid devotees of the Arts and Crafts letterpress tradition, Hamady has never simply "printed books" in the sense of reproducing text on a constipated printed page. Rather, he orchestrates all the components of books into complex "total works of art," so that the end results comprise extraordinary achievements and fall outside the normal realm of what we might hope to encounter in life. Each time he produces a volume (typically in editions of about 100 copies), he cooks up and brings to the table a visual-tactile bouillabaisse of all the facets of book design and production, including inks, paper, color, typesetting, illustration, letterpress printing, binding, marbling and so on.

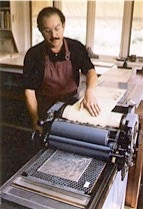

The Perishable Press Limited and the Hamady farm are one and the same geographical spot. Situated sixteen miles southwest of Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, the Minor Confluence Tree Farm (his coinage for the land he owns) is a wild but deliberate natural collage. “All of life is a collage,” he often says, and the farm is a peaceable kingdom he shares with Anna (his devoted wife, who, in his words, is “an engine of compassion and kindness”) and an ever-changing citizenry of bluebirds, wild turkeys, great horned owls, badgers, deer, and hummingbirds. The printing of the books takes place in the house, where his Vandercook press fits snugly in the former parlor. The nearby studio in which he makes collages, box-like assemblages, and exquisite handmade papers (called Shadwell in honor of Thomas Jefferson’s birthplace) is sequestered in the nearby barn.

The Perishable Press Limited was founded in 1964, when Hamady was 24. Under that banner, he has produced (by latest count) 130 limited edition books, thirteen of which were chosen (in the years in which they first came out) by the American Institute of Graphic Arts in New York as among the Fifty Best Books of the year at its prestigious annual showing of the same name. Not surprisingly, his books are now in the collections of the finest libraries, museums and art centers in the world, among them the British Museum, Harvard University, Newberry Library, Oxford University, Yale University, Cleveland Institute of Art, Getty Center, Grolier Club, Lenin Library, Library of Congress, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Royal Library in Stockholm, Sweden, Walker Art Center, Whitney Museum of American Art, Victoria and Albert Museum, and others.

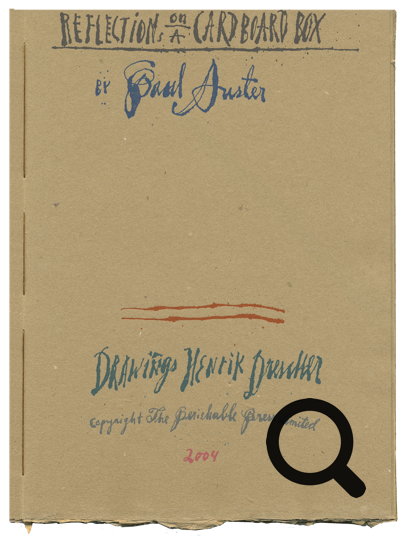

Most of his books have been collaborations, in the sense that they feature the poetry, essays and fiction of some of the finest, most-admired authors of the Modern era, among them Paul Blackburn, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan (collectively known as the Black Mountain poets), Loren Eiseley, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Kenneth Bernard, Clarence Major, Allen Ginsberg, Denise Levertov, Clarence Major, W.S. Merwin, Howard Nemerov, Toby Olson (with whom he’s made eleven books), Richard Wiley, Joel Oppenheimer, Reeve Lindbergh, Jonathan Williams, William Stafford, Bobby Byrd and Paul Auster. Beyond that, they also include drawings, paintings and other provocative images by such extraordinary visual artists as John Wilde (Hamady’s friend for many years), Henrik Drescher, David McLimans, Jim Lee, Peter Sis, Margaret Sunday, Lane Hall and Jack Beal.

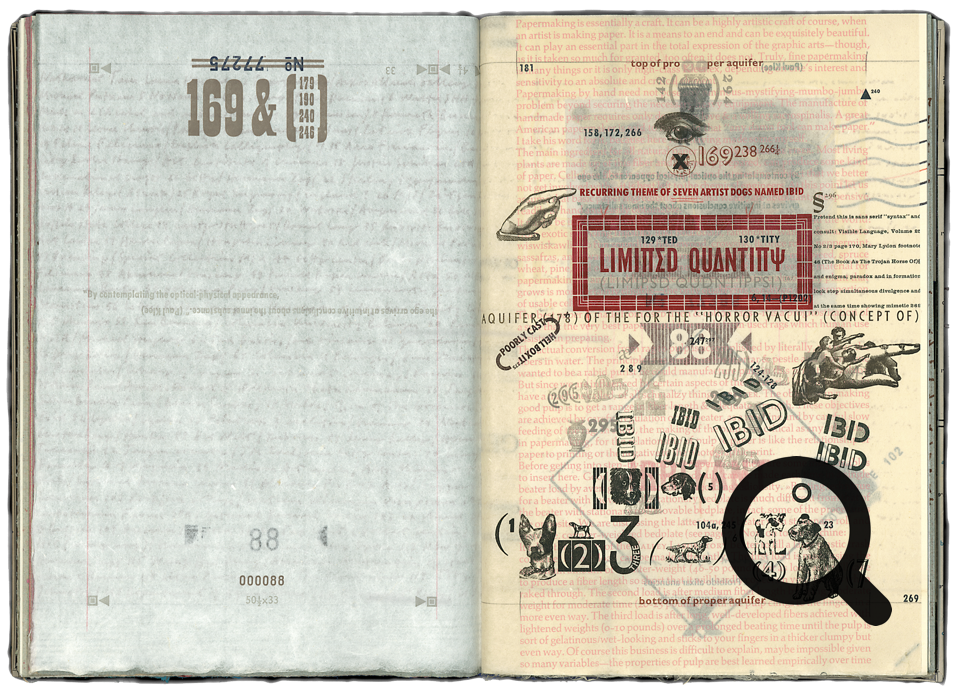

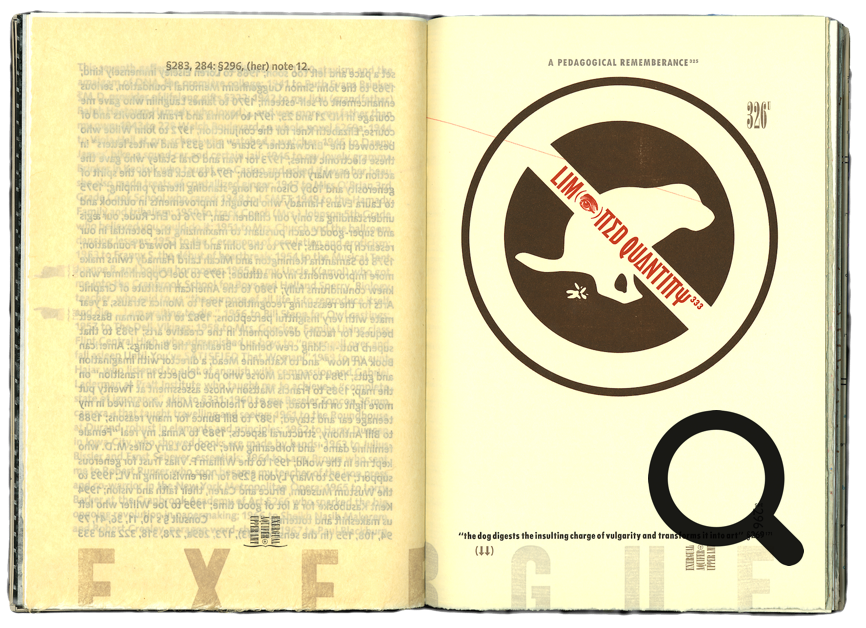

Of Walter’s prodigious productions, none are more widely, repeatedly praised than a series of irreverent, handmade books that he refers to as the Gabberjabbs. Prickly, erratic and gibberish-strewn, they are sardonic pasquinades of pretentious highfalutin research. But they also question their own sanctity, in the sense that while they demonstrate the richness of letterpress printing, they poke fun at traditional notions about the structure and function of books. The book, says Hamady, “is perhaps the most personal form an artist can deal with,” in the sense that it has to be handled individually by each reader, “who then becomes a participant.” It is the “Trojan horse of art,” because a book “is not feared by average people. It is a familiar form in the world, and average people will take it from you and examine it, whereas a painting, poem, sculpture or print they will not.”

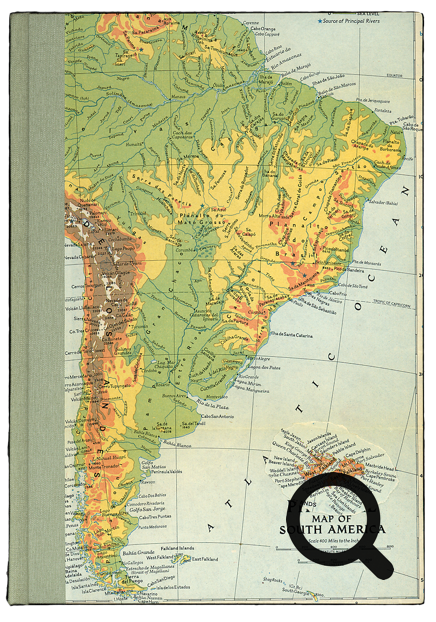

As of 2011, there are eight published Gabberjabbs,* and Hamady has no intention of producing any others. The very first, titled Interminable Gabberjabbs—his sixty-first letterpress book—was published in 1973, the same year that he and his family moved to the Tree Farm. Handset in Sabon-Antiqua and printed in six ink colors on his own Shadwell papers, it extols the virtues of farm life, and celebrates the Blue Mounds zone of the state of Wisconsin. The Blue Mounds, a “driftless” geologic region, was surrounded by the continental glacier but was never completely covered. In this first Gabberjabb, exquisite vintage government geological maps are sewn into each copy.

As the colophon anticipates, this is "the first in a series of playful books that perhaps parody the structure and parts of the book." Partaking of what Walter calls "Hamady heresy," it puns on book nomenclature and belittles the proper arrangement of parts, confessing that the notes section was supposed to have come after the appendix, "but that page wasn't big enough." "We did not have an Appendix," the colophon claims, "so we used an old Uterus instead."

Printed in an edition of 125, each copy of Interminable Gabberjabbs is press-numbered in a fitting but wholly unorthodox way—with a tattooing device for marking cows ears, a tool that Hamady borrowed one Christmas from a neighboring farmer named Ivan Staley. He then dedicated the book to Staley because (according to Hamady) it was Ivan "who got it started & who wryly said, after I showed him how you make paper with your hands: Ith bleev U'd rather milk Cows."

The second and third Gabberjabbs, both published in 1974, are also celebrations of farm life, nature, and the pleasures of growing and harvesting food. Titled Hunkering in Wisconsin and illustrated with Jack Beal’s drawing of a tomato, each copy of the second book is collage-numbered with livestock identification tags. In the third, the harvested crop is the grapeleaf, and its title, Thumbnailing the Hilex, refers to the process of pinching the leaf from its stem. On the title page, a Jack Beal drawing of a grapeleaf is placed within Hamady's parody of a state fair ribbon, described as the Wild Grapeleaf Picking Association Blue Mounds Township Grandprize.

The Interminable Gabberjabb Volume One (&) Number Four, published in 1975, is about domesticity and paternity, and about Hamady’s great satisfaction in cleaning windows with his wife, Mary Laird Hamady, who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Laura (a lawyer in Chicago now). Described by Hamady as having the strongest text of the early Gabberjabbs, it alludes to the fugitive nature of time ("clean glass makes possible views to the past") and the aloneness of creative minds, as described in a passage from Buckthorne by Washington Irving: "Somehow or other, our great geniuses are not gregarious; they do not go in flocks, but fly single in general society… It is only inferior orders that herd together, acquire strength and importance by their confederacies, and bear all the distinctive characteristics of their species."

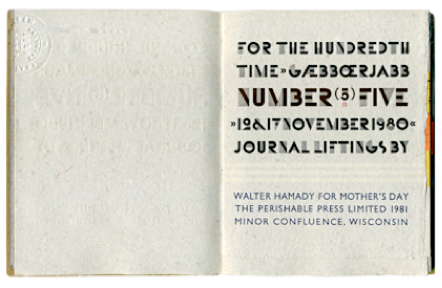

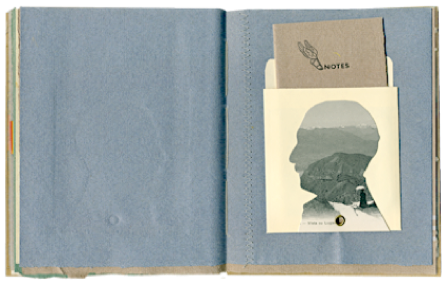

Among Hamady's most admired books is the fifth Gabberjabb. Published in 1981 and titled For The Hundredth Time/Gabberjabb Number Five, it is impeccably handset in Eric Gill’s typeface Gill Sans and A.M. Cassandre's strange Art Deco font called Bifur. The title page is especially memorable, as are the footnotes, which are bound in a miniature booklet and carried in a library card pocket in the back. It is in this Gabberjabb, as the late literary scholar Mary Lydon said in a ponderous scholarly article on Hamady’s work, that his "potential for radically expanding the bookform begins fully to emerge."

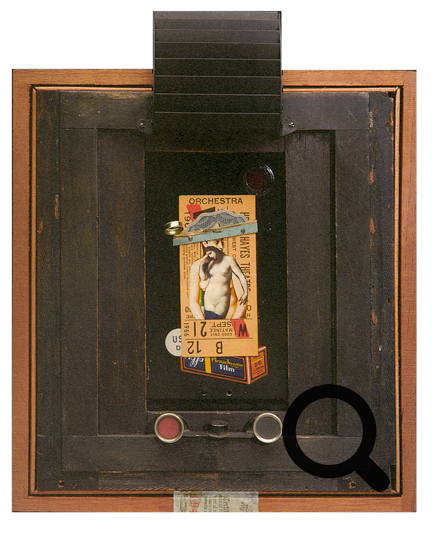

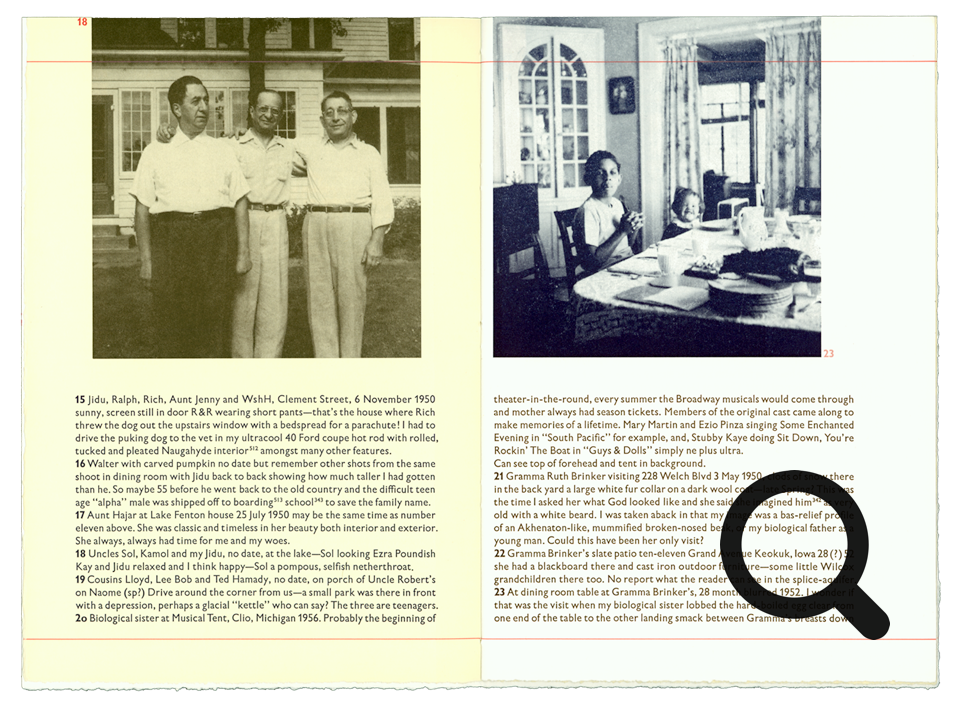

The cover of each copy of the fifth Gabberjabb—there were 200 in the edition—is a one-of-a-kind collage of labels, airplane decals, snapshots, and tickets, while the interior pages are "fastened together or embossed or perforated or rubber-stamped or scored or sewn." While the book is intellectually complex, one critic described it, accurately albeit ironically, as "Hamady's best anti-intellectual effort to date." With the explicit theme of Mother's Day, it is both an appreciation of Hamady's own mother and a recognition of all that Mary his wife had endured in June 1978, when she gave birth to twins: a daughter, Samantha (called Sam), and a son, Micah (both of whom now live in California, where Hamady’s first wife also lives).

Between 1981 and 1988 (an ellipsis of seven years), there were no more Gabberjabbs. The Perishable Press Limited produced only 12 books during that period—slim when compared to its previous pace—while Hamady tried to adapt to a terribly painful divorce, combined with what he labels as (in the sixth Gabberjabb) as the "Disillusionment Disappointment & Disgust or the DDD of midlife crisis in k)academia or Professoring for twenty-two years and earning the $alary of an Entering Assistant Professor which, More or less, Points to several conc(de)lusions."

Judging from the title of this Gabberjabb, called Neopostmodrinism or Dieser Rasen ist kein Hundeklo or Gabberjabb Number 6, it may have been partly his way to respond to the deluge of murky postmodernist fads that contaminated American universities in the 1980s, an academic equivalent to the Red Guard in the People’s Republic of China. The title's foreign language is the text of a street sign that Hamady saw in a railway station in Germany, which translates roughly as "This grass is not a toilet for your dog." In addition, it is a deliberate reference to what Hamady calls his "art as shit" pronouncement, in which he contends that his letterpress concoctions are not merely about printing, but about "the arrangement of things in a given space; stretching and pushing expectations, limits and buttons; finding the extraordinary in the prosaic ordinary and baking bread out of shit but making it taste good."

Whether Hamady is literally baking bread—or making books, writing letters, paper-making, teaching, raising children, building birdhouses, cleaning windows, or planting and harvesting things that he grows—everything he undertakes is about making art out of non-art, or, conversely, making non-art out of art, activities others have often described as "making the familiar strange" and "making the strange familiar." This is an ever-present theme in Hamady's creative process—an approach described poetically by New York book aficionado Steven Clay as "recycling stuff by starlight."

Historically, there is no shortage of precedents for alchemical transformations like these. At the beginning of the 20th century, German advertising designer Lucian Bernhard “enshrined” the banal commercial goods by surrounding them with empty space in posters that acquired the name of Plakatstil, a technique that to some degree anticipated Marcel Duchamp's conversion (in 1917) of a urinal into a “readymade” work of art. In 1918, Dadaist Kurt Schwitters combined wire, rags, and other debris to create his first Merz pictures. Five years later, El Lissitzky made deliberate inappropriate use of dingbats and printers' furniture to illustrate Vladimir Mayakovsky's poetry in For the Voice. But there are many more examples: In 1929, Max Ernst recycled bits and pieces of images from trashy dime novels to create his own (non-verbal) collage novels; and, in the 1940s, Joseph Cornell made box-like visual haikus by the radical juxtaposition of junk.

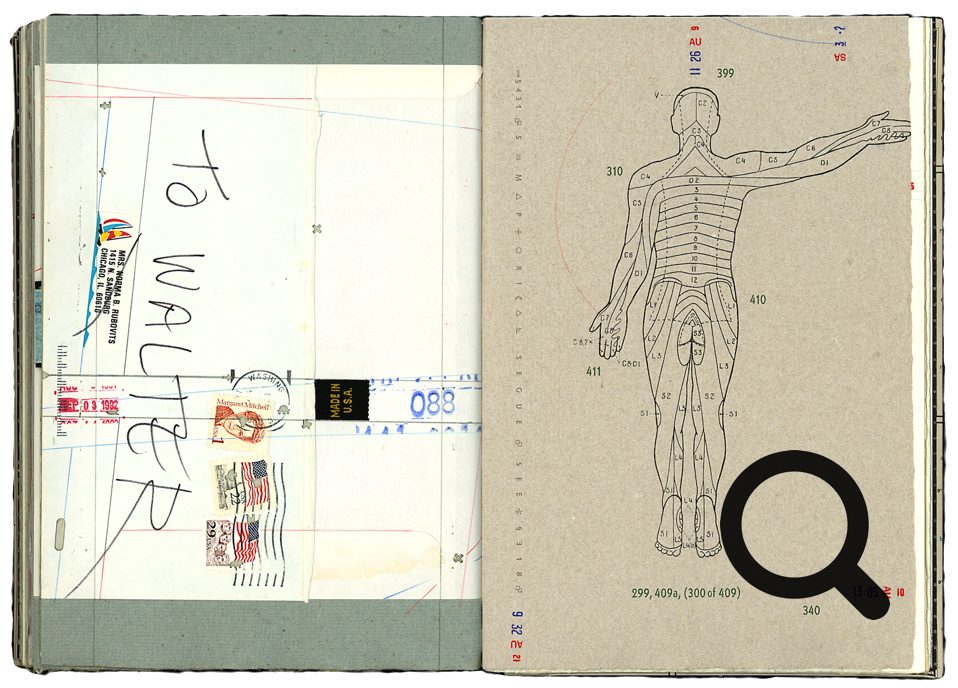

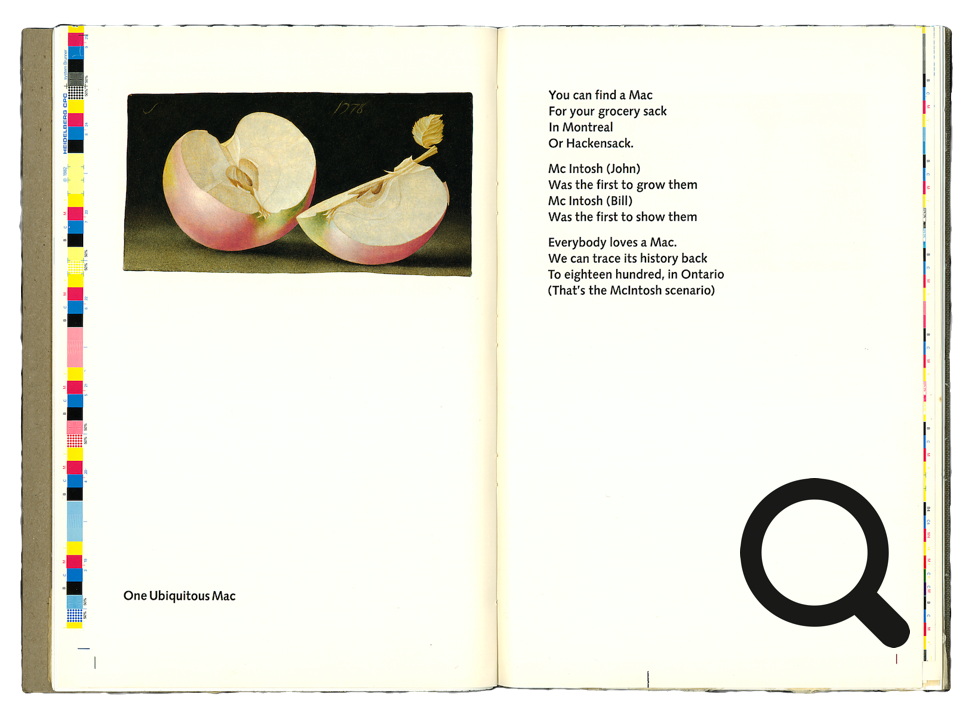

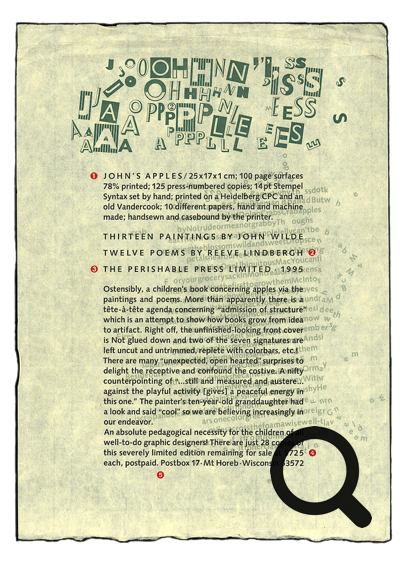

Since the completion of the sixth Gabberjabb in 1989, Hamady has produced seventeen other books, including what might be described as two spin-offs of the Gabberjabbs. The first of these, produced in 1992 and titled 1985: The Twelve Months, was inspired by a stream of consciousness text that emerged from his responses to random rubber-stamp markings in his 1985 journal, bits of which had first appeared in the sixth Gabberjabb. Using that text as a point of departure, Hamady's friend and former university colleague John Wilde created twelve equally enigmatic paintings, one for each month. Wilde and Hamady collaborated again in 1995, in a book for both adults and children (“especially those of well-to-do graphic designers”) titled John’s Apples, which centered on twelve poems about apples by Reeve Lindbergh (the daughter of aviator Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh). By the time of Wilde’s death in 2006, Wilde and Hamady had collaborated on nine books, among them The Story of Jane and Joan (1977), 44 Wilde 1944 (1985), WHMSHW (What His Mother’s Son Hath Wrought) (1988-89), and A Hamady Wilde Sampler/Salutations 1995 (2001).

In 1996, at the end of much personal wrangling, Hamady came out with the seventh Gabberjabb, called Traveling, which he had been struggling with for about five years. It teems with deliberate nonsense, with unabashed mischief and scatological humor. It exemplifies, as noted in its front matter, how "the best books design themselves in a strict sequence of aleatory annexation(s) via fortuitous encounters in incompatible realities." This is of course a reference to Max Ernst’s well-known definition of collage as “the exploitation of the chance meeting on a non-suitable plane of two mutually distant realities,” which was in turn indebted to Comte de Lautréamont’s earlier equation of beauty with “the chance meeting upon a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”

Looking back on all of Hamady’s books, my own sense is that many of the finest were made in the years after 1996, and it seems that the AIGA judges concurred, because, between 1999 and 2006, his books were awarded six medals for being among the Best Fifty Books of the year. The only year in which he did not publish a book was 2005 (and the only year he didn’t win), most likely for the reason that he was putting together the eighth Gabberjabb, titled Hunkering, the Last Gabberjabb. Largely autobiographical, that labyrinthian achievement may be his ultimate tour de force, both for its form and its content.

One sure indicator of Hamady's creative presence (in ways it is this that defines him) is his refusal to permit a thing—or a word or a thought or a tangible form—to remain simply as it is, as if he were haplessly driven to construct, destruct, reconstruct and deconstruct everything: to reshape and reform and restructure to the point that it must be compulsive. Having mastered a skill or traditional craft (such as papermaking, typesetting, letterpress printing, or bookbinding), his immediate impulse is to outdistance that practice; to undermine his own expertise; and to purposely act in a way that is "wrong," to arrive at an end that is even more "right."

For example, in the book of poems and paintings called John's Apples (described earlier), the binding is purposely made to appear unfinished. In another book, titled Nullity (2000), an actual intact letter key from an old typewriter is bound in as part of the cover itself. In yet another recent book, called Depression Dog (2003), there are times when he typesets a page from the text but deliberately fails to stabilize the type, so that the letters are shifted and squeezed. I myself have been the target of his hijinks when, in the seventh Gabberjabb (Traveling), he deliberately shredded a copy of an early, now rare book of mine on Art and Camouflage (1981), then used the ground-up pulp to make a handmade page of paper in each copy of his book—imprinted with the word "camouflage"—so that my book is concealed in his.

Personally, I was first drawn to Hamady's art (his collages, assemblages and handmade books) in the mid-1970s, and thereafter assumed that his genius was on a level that most of us only observe from the sidelines. Thirteen years ago, when I initially sent him a note, it was with great hesitation, since, having assumed that he was eccentric or arrogant, I did not expect to receive a reply. Not only did he answer immediately, he replied with such exuberance that he has never stopped writing, sometimes flooding me with two or three letters in rapid succession, regardless of whether I answered or not.

And just as he burlesques himself by adopting nicknames, he delights in playing comparable tricks on my rural mailman by never addressing his letters to me, but instead to a grab bag of ludicrous names (all of whom apparently reside at my farm), such as Roy Ball Bearings, Corps du Roy, Rhoidamoto, Roy Blastoff Behrens, R Bobo, Roi d'Hoity Toit, Bobbing Links Golf Course Books, King Roi of the Bare Wrens Hens, and so on. On one occasion in particular, a heavily insured package arrived from The Perishable Press Limited containing a review copy of his latest book, but it could not be fully delivered until it was signed for by myself, the addressee, who was listed on the package as Bob O Bare Ends. Accustomed to Hamady's unmistakable handwriting, and savvy to his postal pranks, my stalwart mailman did not flinch.

In all of Hamady’s books, his mastery of color is a conspicuous virtue, and yet it would be wrong to say that his books are "colorful" in a mere prosaic, simple sense. He uses color in his books in a way that is skillfully nuanced, by which I mean that he applies the most whispered distinctions (it reminds me of the well-known phrase "just-noticeable differences"). In some cases, the contrasts are so understated, so slight that most likely only those who see the most fundamental color attributes (hue, value and saturation) at a level of subtle discernment that parallels that of a wine taster, will notice the adroit ingenious forms that he creates by placing on a page, for example, the slightest warm off-white, against a textured cool off-white, against an ink that hints of green, and so forth.

Walter Hamady's letterpress books are “about” many things, far too entangled to try to unfold in a single writing. I would urge anyone who is genuinely curious about such phenomena to move beyond just reading about his books or looking at photographs of them, but somehow to find an immediate way of touching at least one of them. Nothing can substitute for the experience of holding in ones hands an object as unforgettable as a book from The Perishable Press Limited. There is no way to equal the feeling of the marvelous tooth of the imprinted sheet, seeing the rise and the fall of the ink—and (most importantly) slowly but joyfully turning the page to the next welcome surprise.